The New York Public Library recently announced that it has digitized the "List of Loyalists Whom Judgments Were Given Under the Confiscation Act". This document is a list of judgments against loyalists in New York State following the passage of the Confiscation Act of 1779. The document includes the names of the loyalists convicted, their occupations, the town or county that they resided in, dates of indictment, and dates of judgment. The indictment dates and judgments span 1780-1783.

A casual review of the list reveals that the majority of these loyalists were from the middle and lower classes of society. Many are listed simply as "yeoman" and "laborers". Of course, this list underscores the need to destroy the popular myth that most loyalists were corrupt, inept, greedy people whose blind faith to the British crown led to their downfall. Such erroneous stereotypes only undermine and trivialize the struggles of the American loyalist.

By the conclusion of the American Revolution, between 80,000 and 100,000 loyalists had fled the American colonies. Almost half of them escaped to Canada. Of those, 45,000 refugees settled in the Canadian Maritime region. An additional 9,500 refugees fled to the Quebec province. From Quebec, 7,500 loyalists ultimately settled in Upper Canada. These men, women and children that fled the American colonies left behind more than their homes. They left behind their experiences, personal belongings, communities, friends and relatives.

Many colonists who ultimately became “Tories” were not distinguishable from their neighbors who embraced independence. Many loyalists were respected members of their towns; often well-educated Harvard graduates who worked as merchants, doctors, lawyers, distillers or ministers. Individuals such as Sir John Johnson, Richard Saltonstall, Jonathan Sewell and Admiralty Judge Samuel Curwen, who would later enlist in the loyalist cause, were seen prior to the American Revolution as leading and influential members their respective colonies.

However, most colonists from New York and New England who remained faithful to the crown hailed from the middle and lower classes of the American colonies. These loyalists enjoyed neither wealth nor privilege. Of the four hundred eighty-eight loyalists who eventually settled in the Ontario region of Upper Canada and submitted claims to the British government for losses sustained during the American Revolution, only five held public office. Three were considered modest political posts. Only one claimant, a physician, would be considered a professional by modern standards. A small number owned shops, ran taverns or were considered artisans. Ninety percent of those loyalists who settled in the Ontario region simply identified themselves as farmers.

The average loyalist farmer who ultimately took refuge in Upper Canada leased or owned less than two hundred acres of land prior to the American Revolution. Forty-two percent of the Ontario settlers admitted they had cleared less than ten acres of land prior to their flight. Fifty-four percent of the farmers hailed from Tyron County, New York. An additional twenty-five percent had ties to Albany County. Fourteen percent claimed Charlotte County as their prior residence.

Over half of the refugees who settled in Upper Canada were foreign born. Over fifty percent of Ontario loyalists were Scot Highland Roman Catholics. Second in number were German and Irish immigrants. An additional eight percent claimed England as their place of birth. Many did not speak English. Many loyalist Scot immigrants had only resided in the American colonies for four years at the start of the American Revolution. English immigrants had resided in America on average for eight years. By comparison, many Irish and German immigrants had lived in the colonies between eleven and eighteen years.

Joining these loyalists were African-American loyalists. Almost ten percent of loyalists that fled to Canada were of African-American descent. Whether slave or freeman, many African-Americans cast their lot with the crown in an attempt to secure a better life for themselves and their families. Likewise, many Native American allies of the crown also retreated to Canada after the war. Over two thousand Iroquois from the Six Nations, Mohicans, Nanticokes and Squakis had settled in the Ontario region by 1785.

Regardless of their economic or social background, native born whites, immigrants, slaves, freemen and Native Americans banded together in support of King George and the British government. Regardless of the lack of supplies, political support or financial backing, the campaign to defend the British crown was enthusiastically and admirably waged by loyalists from the print of local newspapers to the siege lines of Yorktown. Granted, their defense of British policy often fell on deaf ears and their military endeavors were often insufficient to turn the tide of war, their willingness to undertake such endeavors is noteworthy.

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

Friday, January 27, 2017

"Best to the Reliefe of Our Friend[s] and Country" - Amesbury's War Effort on the Eve of Lexington and Concord

In 1774, many Massachusetts towns undertook sweeping measures to prepare for war with England. Surprisingly, Amesbury was not one of those towns. A review of original town records currently housed at the Amesbury City Hall reveal that the citizens of that town dragged their feet and waited until the last minute to form a minute company.

In 1774, while the neighboring towns were reorganizing its militia companies and forming an artillery unit, Amesbury merely elected to inspect its supply of gunpowder and ammunition. When officials opened the West Parish powder house (Amesbury had at least two powder houses in 1775), they were horrified to discover the entire supply missing. No immediate effort was made to replace or recover the lost ammunition.

In January and February, 1775, Samuel Johnson, the regimental commander of the 4th Essex Regiment, ordered towns under his command, including Amesbury, to form minute companies. Andover, Methuen, Bradford, Boxford, Haverhill and Salisbury quickly complied. For example, on February 22, 1775, Johnson visited Boxford. The colonel “addressed himself with great zeal to the two foot-companies of the Fourth Regiment, recommending to them the necessity of enlisting themselves into the service of the Province, and in a short space of time fifty-three able-bodied and effective men willingly offered themselves to serve their Province in defence of their liberties.”

Amesbury never acted upon Johnson's instructions and thus, failed to form a minute company in early 1775.

It would not be until the first week of March that Amesbury hosted a town meeting to address the question of whether a minute company should be raised. After some discussion, the town unexpectedly voted NOT to form a unit. Of course, in the tradition of New England town meetings when one does not like the outcome of a vote, you have another meeting and pack it with supporters. At a second meeting on March 20, 1775, the town finally “voted to raise fifty able bodyed men including officers for minnit men and to enlist them for one year.” By April 19th the town had raised two minute companies.

Why was Amesbury so reluctant to form a minute company?

It is possible the town felt it could not financially support such an endeavor. It's supply of ammunition and gunpowder was still depleted. Where other towns resolved to purchase and provide arms and equipment for their minute men, Amesbury voted "that said Minnit men shall upon their own cost be well equiped with arms and aminition according to law fit for a march.” Likewsie, most communities offered substantial compensation for minutemen who drilled and responded to emergencies. Amesbury offered much cheaper compensation rates. "Each man shall have one shilling for exercising four hours in an fortnight and that the commanding officer of said Minnit men shall exhibit an account of them that shall exercise to the Selectmen for to receive their pay for exercising . . .each minit man shall have two dollars bounty paid them at their first marching of provided they are called for by the Congress or a General officer they may appoint.”

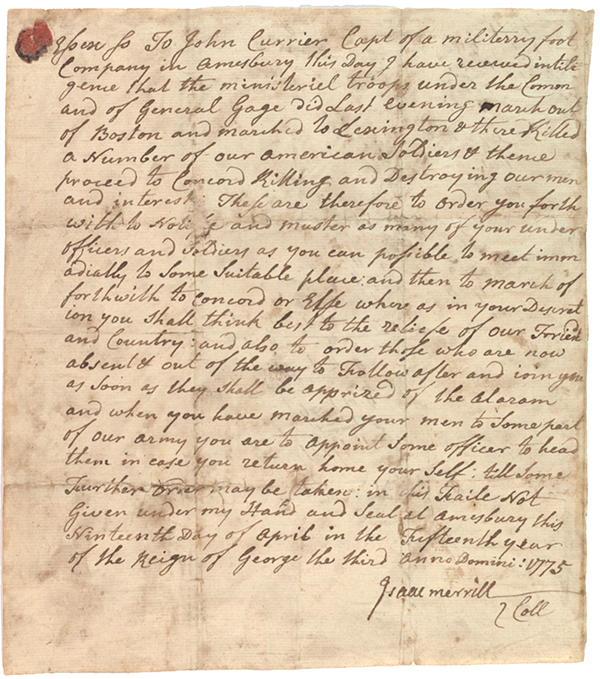

Despite these financial and supply restrictions Amesbury's minute and militia companies did successfully mobilize for war on April 19, 1775. About mid morning, Amesbury's representative to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, Isaac Merrill, received news of the Battle of Lexington. He immediately drafted correspondence to the captains of the Amesbury Minute Companies and ordered them to mobilize:

“Essex Co To John Currier Capt of a militerry foot Company in Amesbury this Day I have received intiligence that the ministeriel troops under the Command of General Gage did Last evening march out of Boston and marched to Lexington & there Killed a Number of our American Soldiers & thence proceed to Concord Killing and Destroying our men and interest: These are therefore to order you forthwith to Notify and muster as many of your under officers and Soldiers as you can possible to meet immediatly to Some Suitable place: and then to march of forthwith to Concord or Else where as in your Descretion you Shall think best to the reliefe of our Friend[s] and Country: and also to order those who are now absent & out of the way to Follow after and ioin you as Soon as they shall be apprized of the Alaram and when you have marched your men to Some part of our army you are to appoint some officer to head them in case you return home your Self: till Some Further order may be taken: in this Faile Not Given under my Hand and Seal at Amesbury this Ninteenth Day of April in the Fifteenth year of the Reign of George the third Anno Domini: 1775. Isaac Merrill.”

Although Amesbury's men did not catch the retreating regulars, they did actively participate in the Siege of Boston as part of Colonel Frye's Regiment. Period accounts suggest that the men participated in the Battle of Chelsea Creek and fought inside the redoubt at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

In 1774, while the neighboring towns were reorganizing its militia companies and forming an artillery unit, Amesbury merely elected to inspect its supply of gunpowder and ammunition. When officials opened the West Parish powder house (Amesbury had at least two powder houses in 1775), they were horrified to discover the entire supply missing. No immediate effort was made to replace or recover the lost ammunition.

In January and February, 1775, Samuel Johnson, the regimental commander of the 4th Essex Regiment, ordered towns under his command, including Amesbury, to form minute companies. Andover, Methuen, Bradford, Boxford, Haverhill and Salisbury quickly complied. For example, on February 22, 1775, Johnson visited Boxford. The colonel “addressed himself with great zeal to the two foot-companies of the Fourth Regiment, recommending to them the necessity of enlisting themselves into the service of the Province, and in a short space of time fifty-three able-bodied and effective men willingly offered themselves to serve their Province in defence of their liberties.”

Amesbury never acted upon Johnson's instructions and thus, failed to form a minute company in early 1775.

It would not be until the first week of March that Amesbury hosted a town meeting to address the question of whether a minute company should be raised. After some discussion, the town unexpectedly voted NOT to form a unit. Of course, in the tradition of New England town meetings when one does not like the outcome of a vote, you have another meeting and pack it with supporters. At a second meeting on March 20, 1775, the town finally “voted to raise fifty able bodyed men including officers for minnit men and to enlist them for one year.” By April 19th the town had raised two minute companies.

Why was Amesbury so reluctant to form a minute company?

It is possible the town felt it could not financially support such an endeavor. It's supply of ammunition and gunpowder was still depleted. Where other towns resolved to purchase and provide arms and equipment for their minute men, Amesbury voted "that said Minnit men shall upon their own cost be well equiped with arms and aminition according to law fit for a march.” Likewsie, most communities offered substantial compensation for minutemen who drilled and responded to emergencies. Amesbury offered much cheaper compensation rates. "Each man shall have one shilling for exercising four hours in an fortnight and that the commanding officer of said Minnit men shall exhibit an account of them that shall exercise to the Selectmen for to receive their pay for exercising . . .each minit man shall have two dollars bounty paid them at their first marching of provided they are called for by the Congress or a General officer they may appoint.”

Despite these financial and supply restrictions Amesbury's minute and militia companies did successfully mobilize for war on April 19, 1775. About mid morning, Amesbury's representative to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, Isaac Merrill, received news of the Battle of Lexington. He immediately drafted correspondence to the captains of the Amesbury Minute Companies and ordered them to mobilize:

“Essex Co To John Currier Capt of a militerry foot Company in Amesbury this Day I have received intiligence that the ministeriel troops under the Command of General Gage did Last evening march out of Boston and marched to Lexington & there Killed a Number of our American Soldiers & thence proceed to Concord Killing and Destroying our men and interest: These are therefore to order you forthwith to Notify and muster as many of your under officers and Soldiers as you can possible to meet immediatly to Some Suitable place: and then to march of forthwith to Concord or Else where as in your Descretion you Shall think best to the reliefe of our Friend[s] and Country: and also to order those who are now absent & out of the way to Follow after and ioin you as Soon as they shall be apprized of the Alaram and when you have marched your men to Some part of our army you are to appoint some officer to head them in case you return home your Self: till Some Further order may be taken: in this Faile Not Given under my Hand and Seal at Amesbury this Ninteenth Day of April in the Fifteenth year of the Reign of George the third Anno Domini: 1775. Isaac Merrill.”

Although Amesbury's men did not catch the retreating regulars, they did actively participate in the Siege of Boston as part of Colonel Frye's Regiment. Period accounts suggest that the men participated in the Battle of Chelsea Creek and fought inside the redoubt at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Monday, January 23, 2017

"We Stopt to Polords & Eat Some Bisket & Ches on the Comon" - How the Andover Minute Men Missed an Opportunity to Attack the British

In the early morning of April 19, 1775, news of a British operation towards Concord reached the Merrimack Valley. As militia and minute companies assembled, the Valley town that had the best chance of catching and engaging the British column was Andover.

Andover was the westernmost town in Essex County and was less than twenty miles away from both Concord and Lexington. On April 19th, it had two minute companies and four militia companies.

Andover was the westernmost town in Essex County and was less than twenty miles away from both Concord and Lexington. On April 19th, it had two minute companies and four militia companies.

According to Lieutenant Benjamin Farnum the Andover minute companies quickly mobilized. "April 19, 1775. This day, the Mittel men . . . were Alarmed with the Nuse of the Troops marching from Boston to Concord, at which Nuse they marched very quick from Andover, and marched within about 5 miles of Concord, then meeting with the Nuse of their retreat for Boston again with which Nuse we turned our corse in order to catch them."

Likewise, Andover minute man Thomas Boynton described how his unit shifted course multiple times in an attempt to catch up with the regulars. "Andover, April 19, 1775. This morning, being Wednesday, about the sun's rising the town was alarmed with the news that the Regulars was on their march to Concord. Upon which the town mustered and . . . marched onward for Concord. In Tewksbury news came that the Regulars had fired on our men in Lexington, and had killed 8. In Bilricke news came that the enemy were killing and slaying our men in Concord. Bedford we had the news that the enemy had killed 2 of our men and had retreated back; we shifted our course and persued after them as fast as possible, but all in vain ; the enemy had the start 3 or 4 miles."

Given the statements of Bonton and Farnum, one might ask why was Andover unsuccessful in intercepting Lieutenant Colonel Smith's column that day. Did the Andover minute companies take a wrong turn or become lost as they marched further into Middlesex County?

No - they were simply hungry.

According to James Stevens, the men only marched through two towns and then stopped for lunch. Afyer halting, they ate biscuits and cheese on a common across from Solomon Pollard's Tavern in Billerica.

"April ye 19 1775 this morning about seven aclok we had alarum that the Reegerlers was gon to Conkord we getherd to the meting hous & then started for Concord we went throu Tukesbary & in to Bilrica we stopt to Polords & eat some bisket & Ches on the comon."

According to James Stevens, the men only marched through two towns and then stopped for lunch. Afyer halting, they ate biscuits and cheese on a common across from Solomon Pollard's Tavern in Billerica.

"April ye 19 1775 this morning about seven aclok we had alarum that the Reegerlers was gon to Conkord we getherd to the meting hous & then started for Concord we went throu Tukesbary & in to Bilrica we stopt to Polords & eat some bisket & Ches on the comon."

The men must have spent considerable time eating in Billerica as they missed any chance of intercepting the enemy. When the Andover men finally resumed their march, they quickly learned that the British troops had already joined Lord Percy's relief column, left Lexington and were en route back to Boston. According to Stevens:

"We started & wen into Bedford & we herd that the regerlers was gon back to Boston we went through Bedford, we went in to Lecentown. We went to the metinghous & there we come to the distraction of the Reegerlers thay cild eight of our men & shot a Canon Ball throug the metin hous. we went a long through Lecintown & we saw severel regerlers ded on the rod & som of our men & three or fore houses was Burnt & som hoses & hogs was cild thay plaindered in every hous thay could git in to thay stove in windows & broke in tops of desks we met the men a coming back very fast we went through Notemy & got into Cambridg we stopt about eight acloke for thay say that the regerlers was got to Chalstown on to Bunkers hil & intrenstion we stopt about two miles back from the college."

"We started & wen into Bedford & we herd that the regerlers was gon back to Boston we went through Bedford, we went in to Lecentown. We went to the metinghous & there we come to the distraction of the Reegerlers thay cild eight of our men & shot a Canon Ball throug the metin hous. we went a long through Lecintown & we saw severel regerlers ded on the rod & som of our men & three or fore houses was Burnt & som hoses & hogs was cild thay plaindered in every hous thay could git in to thay stove in windows & broke in tops of desks we met the men a coming back very fast we went through Notemy & got into Cambridg we stopt about eight acloke for thay say that the regerlers was got to Chalstown on to Bunkers hil & intrenstion we stopt about two miles back from the college."

It is unknown what the result would have been if the Andover Minute Companies had successfully caught up to the British column. Nevertheless, the decision to stop for lunch resulted in at least two minute companies missing an opportunity to attack the regulars as they fought their way back to Boston.

Monday, January 16, 2017

Militia Laws, Resolutions and Minute Men - Five Important Facts to Remember about the 1774-1775 American War Effort

This past weekend, we at Historical Nerdery had the opportunity to share our research on Pre-Lexington and Concord militia laws at a workshop sponsored by Minute Man National Historic Park and the Concord Museum.

Here are five (5) important points we felt should be shared with you as well:

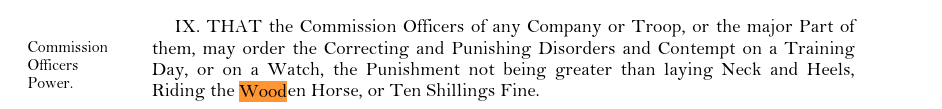

Militia Laws were detailed and had teeth. Massachusetts Militia Laws were 17th and 18th century legal statutes that were drafted and passed by the legislature of Massachusetts Bay Colony. However, these laws were not simply about listing what equipment a militiaman should own and carry into the field. Instead, militia laws also addressed who was expected to serve in the militia, under what circumstances a militia company would assemble for an "alarm", what authority was vested in company officers and what penalties could be imposed in the event of a violation.

Despite what many modern authors assert, Massachusetts militia laws of the 17th and 18th centuries carried criminal penalties, including the imposition of a fine or physical punishment. Period accounts absolutely establish the laws were ENFORCED.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress only issued recommendations. As tensions mounted during the fall of 1774, the Provincial Congress began to pass a series of resolutions that, if followed, would better prepare the militia for a potential conflict with England.

The relevant resolution states “The improvement of the militia in general in the art military has been therefore thought necessary, and strongly recommended by this Congress. We now think that particular care should be taken by the towns and districts in this colony, that each of the minute men, not already provided therewith, should be immediately equipped with an effective firearm, bayonet, pouch, knapsack, thirty rounds of cartridges and balls.”

These resolves were not laws and did not alter the old militia acts. Rather, they were recommendations that worked within the existing militia framework. It is likely the organization chose the phrase "recommend" so as to avoid the appearance of being in open rebellion against the Crown and Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Town responses to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress' recommendations. Following the recommendations of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, most Massachusetts towns elected to pass resolves adopting Congress’ “recommendations”. These town laws ordered what its respective minute and militia companies would be armed and equipped with.

It is likely the towns took it upon themselves to pass these regulations because the colonial legislature was in legal and political limbo and the Massachusetts Provincial Congress stood on shaky authoritative ground.

The resolutions we researched seemed to fall into three categories:

Local men were helping minute and militia companies ensure they were properly armed, supplied and equipped. Local men were hired by their respective towns to make certain pieces of equipment for the militia and minute companies. One resident may have made cartridge boxes for his town’s minute company while another made bayonet carriages. For example, Springfield's Ariel Collins was paid £1. Is. 6d for making "43 cartouch-boxes". Phineas Carlton of Bradford was paid for scouring 22 bayonets and fitting them with scabbards and belts. John Parker of Lexington was possibly making powder horns.

As a result of these efforts, there was some semblance of equipment uniformity among the American minute on the eve of Lexington and Concord.

On April 19, 1775, the Massachusetts militia and minute companies to the field armed and equipped for a military campaign. Many 19th and 20th century paintings depict the "embattled farmer" armed only with a musket and powder horn. This is simply not correct. The men who fielded on April 19th were equipped with arms and accouterments, including knapsacks, blankets and canteens. In a report to General Gage regarding the Battle of Lexington, the officer stated "On these companies' arrival at Lexington, I understand, from the report of Major Pitcairn, who was with them, and from many officers, that they found on a green close to the road a body of the country people drawn up in military order, with arms and accoutrement, and, as appeared after, loaded."

Here are five (5) important points we felt should be shared with you as well:

Militia Laws were detailed and had teeth. Massachusetts Militia Laws were 17th and 18th century legal statutes that were drafted and passed by the legislature of Massachusetts Bay Colony. However, these laws were not simply about listing what equipment a militiaman should own and carry into the field. Instead, militia laws also addressed who was expected to serve in the militia, under what circumstances a militia company would assemble for an "alarm", what authority was vested in company officers and what penalties could be imposed in the event of a violation.

Despite what many modern authors assert, Massachusetts militia laws of the 17th and 18th centuries carried criminal penalties, including the imposition of a fine or physical punishment. Period accounts absolutely establish the laws were ENFORCED.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress only issued recommendations. As tensions mounted during the fall of 1774, the Provincial Congress began to pass a series of resolutions that, if followed, would better prepare the militia for a potential conflict with England.

The relevant resolution states “The improvement of the militia in general in the art military has been therefore thought necessary, and strongly recommended by this Congress. We now think that particular care should be taken by the towns and districts in this colony, that each of the minute men, not already provided therewith, should be immediately equipped with an effective firearm, bayonet, pouch, knapsack, thirty rounds of cartridges and balls.”

These resolves were not laws and did not alter the old militia acts. Rather, they were recommendations that worked within the existing militia framework. It is likely the organization chose the phrase "recommend" so as to avoid the appearance of being in open rebellion against the Crown and Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Town responses to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress' recommendations. Following the recommendations of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, most Massachusetts towns elected to pass resolves adopting Congress’ “recommendations”. These town laws ordered what its respective minute and militia companies would be armed and equipped with.

It is likely the towns took it upon themselves to pass these regulations because the colonial legislature was in legal and political limbo and the Massachusetts Provincial Congress stood on shaky authoritative ground.

The resolutions we researched seemed to fall into three categories:

- Vague, often last minute, resolutions passed by towns after January, 1775 that likely relied upon existing militia laws.

- Highly detailed resolutions that often expanded upon or added to the recommendations of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress as to what a militiaman or minuteman should carry.

- Resolutions and contractual clauses drafted and issued by “independent” minute companies from several Massachusetts towns.

Local men were helping minute and militia companies ensure they were properly armed, supplied and equipped. Local men were hired by their respective towns to make certain pieces of equipment for the militia and minute companies. One resident may have made cartridge boxes for his town’s minute company while another made bayonet carriages. For example, Springfield's Ariel Collins was paid £1. Is. 6d for making "43 cartouch-boxes". Phineas Carlton of Bradford was paid for scouring 22 bayonets and fitting them with scabbards and belts. John Parker of Lexington was possibly making powder horns.

As a result of these efforts, there was some semblance of equipment uniformity among the American minute on the eve of Lexington and Concord.

On April 19, 1775, the Massachusetts militia and minute companies to the field armed and equipped for a military campaign. Many 19th and 20th century paintings depict the "embattled farmer" armed only with a musket and powder horn. This is simply not correct. The men who fielded on April 19th were equipped with arms and accouterments, including knapsacks, blankets and canteens. In a report to General Gage regarding the Battle of Lexington, the officer stated "On these companies' arrival at Lexington, I understand, from the report of Major Pitcairn, who was with them, and from many officers, that they found on a green close to the road a body of the country people drawn up in military order, with arms and accoutrement, and, as appeared after, loaded."

Friday, January 6, 2017

"That Bayonets Are of More Use, as Well for Offence as Defence" - The Availability of Bayonets in Pre-Revolutionary War Massachusetts Revisted

Back in December, Historical Nerdery posted an article on the availability of bayonets in Pre-Revolutionary War Massachusetts. At the time, one of the assertions we made was Massachusetts militiamen were very reluctant to adopt bayonets. We went even further and argued early colonial government policy actually discouraged the use of bayonets.

However, in 1757, the Massachusetts General Court passed a law ordering that half of the men enlisted in the colony's militia companies be issued bayonets at the expense of the government. Specifically, the resolution stated "Be it further enacted, That one half of the Non-Commission Officers and private Soldiers, liable to train, shall be furnished with a good Bayonet with a Steel Blade, not less than fifteen Inches long, fitted to his Gun, with a Scabbard for the same, for which Bayonet and Scabbard there shall be paid out of the publick Treasury not exceeding seven Shillings; and that the Captain or chief Officer of each Foot Company, shall take effectual Care that they be so provided; and an Account thereof shall be presented by said Officer to the Governour and Council for Allowance and Payment; for which Bayonet and Scabbard each Non-Commission Officer and Soldier so provided, shall be accountable to this Government, unless under the Age of twenty-one Years; and for such as are Minors their Parents, Guardians or Masters respectively shall be so accountable: and each Non Commission Officer and Soldier (Drummers excepted) shall upon every training Day Muster, Review or Alarm (after they are provided with Bayonets as aforesaid) appear with the same, on Penalty of two Shillings for each Neglect."

Unfortunately, it is unknown how successful this law was in getting bayonets into the hands of militiamen. It took Lexington over two years to issue bayonets to forty-nine of its militiamen. In 1759, Captain Benjamin Reed notified the colony "[the] following names are a full and Just account of those to whom I the Subscriber delivered Bayonets in the company under my command in Lexington . . . June 5, 1759… [49 militia men listed]”.

Given the returns of militia and minute companies on the eve of Lexington and Concord and the efforts of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to secure bayonets, it's likely the 1757 law had little impact.

We would like to make a slight correction based upon some of our findings over the winter break.

It appears that on at least two occasions between 1690 and 1774, Massachusetts Bay Colony did make half-hearted attempts to ensure some of its militia men were issued bayonets.

In 1713, the Massachusetts General Court passed a law ordering militia men from Boston who did not own swords or cutlasses to be provided with bayonets. "Every Listed Soldier, and other Householder (except "Troopers") is to be provided with a good Sword or Cutlash, under Penalty in the said Act . . . And whereas it is found by Experience, That Bayonets are of more Use, as

well for Offence as Defence; Be it therefore Enacted by the Governor, Council, and

Representatives, in General Court assembled, and by the Authority of the same, That,

from and after the Twentieth Day of June next, every Person in the Town of Boston, who

is obliged by the aforesaid Act to appear upon an Alarm at the Place of Rendezvous, or

where the Chief Officer doth appoint, (except Troopers) shall be provided with a good

Goose-necked Bayonet with Socket, fit to fix over the Muzzle of his Musket, under the

like Penalty, as in the said Act is mentioned, for not being provided with a Sword or

Cutlash."

From the text of this resolution, it is clear that bayonets were a "secondary choice" and were only issued to men who resided in Boston. As a result, one could argue that once again early colonial government policy discouraged the widespread use of bayonets.

|

| 18th C. Bayonet, Old Newbury Museum |

However, in 1757, the Massachusetts General Court passed a law ordering that half of the men enlisted in the colony's militia companies be issued bayonets at the expense of the government. Specifically, the resolution stated "Be it further enacted, That one half of the Non-Commission Officers and private Soldiers, liable to train, shall be furnished with a good Bayonet with a Steel Blade, not less than fifteen Inches long, fitted to his Gun, with a Scabbard for the same, for which Bayonet and Scabbard there shall be paid out of the publick Treasury not exceeding seven Shillings; and that the Captain or chief Officer of each Foot Company, shall take effectual Care that they be so provided; and an Account thereof shall be presented by said Officer to the Governour and Council for Allowance and Payment; for which Bayonet and Scabbard each Non-Commission Officer and Soldier so provided, shall be accountable to this Government, unless under the Age of twenty-one Years; and for such as are Minors their Parents, Guardians or Masters respectively shall be so accountable: and each Non Commission Officer and Soldier (Drummers excepted) shall upon every training Day Muster, Review or Alarm (after they are provided with Bayonets as aforesaid) appear with the same, on Penalty of two Shillings for each Neglect."

Unfortunately, it is unknown how successful this law was in getting bayonets into the hands of militiamen. It took Lexington over two years to issue bayonets to forty-nine of its militiamen. In 1759, Captain Benjamin Reed notified the colony "[the] following names are a full and Just account of those to whom I the Subscriber delivered Bayonets in the company under my command in Lexington . . . June 5, 1759… [49 militia men listed]”.

Given the returns of militia and minute companies on the eve of Lexington and Concord and the efforts of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to secure bayonets, it's likely the 1757 law had little impact.