In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act in an attempt to refinance the shaky economic base of the British East India Company. Established in 1709, the East India Company derived over ninety-percent of its profits from the sale of tea. However, by 1772, due to severe mismanagement, the company was in desperate need of a bailout. The company directors looked to Parliament for relief. Parliament’s response was the Tea Act, through which the East India Company was given exclusive rights to ship tea to America without paying import duties and to sell it through their agents to American retailers. American merchants who had for years purchased tea from non-British sources (Dutch tea was a particular favorite of New Englanders) faced the prospect of financial ruin.

Massachusetts immediately opposed the act and began to organize resistance. On November 29, 1773, the tea ship Dartmouth arrived at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston. Three days later, the Beaver and the Eleanor arrived at the same wharf. Bostonians demanded that Governor Hutchinson order the three ships back to England. On December 16, 1773, the owner of the Dartmouth apparently agreed and went to Hutchinson to beg him to let the ships return to England. Hutchinson refused, and at approximately six o’clock that evening, some 150 men and boys disguised as Indians marched to the three ships, boarded them and dumped 340 chests of tea into Boston Harbor.

Meanwhile, as tempers boiled over in Boston, the citizens of Lexington assembled three days prior to the Boston Tea Party to discuss the unfolding events. The matter was referred to the town’s committee of correspondence, which quickly drafted an emotional and stinging condemnation of the Tea Act.

"[It] appears that the Enemies of the Rights & Liberties of Americans, greatly disappointed in the Success of the Revenue Act, are seeking to Avail themselves of New, & if possible, Yet more detestable Measures to distress, Enslave & destroy us. Not enough that a Tax was laid Upon Teas, which should be Imported by Us, for the Sole Purpose of Raising a revenue to support Taskmasters, Pensioners, &c., in Idleness and Luxury; But by a late Act of Parliament, to Appease the wrath of the East India Company, whose Trade to America had been greatly clogged by the operation of the Revenue Acts, Provision is made for said Company to export their teas to America free and discharged from all Duties and Customs in England, but liable to all the same Rules, Regulations, Penalties & Forfeitures in America, as are Provided by the Revenue Act . . . Not to say anything of the Gross Partiality herein discovered in favour of the East India Company, and to the Injury & oppression of Americans; . . . we are most especially alarmed, as by these Crafty Measures of the Revenue Act is to be Established, and the Rights and Liberties of Americans forever Sapped & destroyed. These appear to Us to be Sacrifices we must make, and these the costly Pledges that must be given Up into the hands of the Oppressor. The moment we receive this detested Article, the Tribute will be established upon Us . . . Once admit this subtle, wicked Ministerial Plan to take place, once permit this Tea . . . to be landed, received and vended . . . the Badge of our slavery is fixed, the Foundation of ruin is surely laid. "

The committee also issued six resolves pledging to preserve and protect the constitutional rights that Parliament had put into jeopardy, to boycott any teas "sent out by the East India Company, or that shall be imported subject to a duty imposed by Act of Parliament," to treat as enemies anyone found aiding in the landing, selling or using of tea from the East India Company, and to treat the merchants of the East India Company with contempt. Finally, the town expressed its gratitude to Boston for its undertaking in the name of liberty, and pledged

"We are ready and resolved to concur with them in every rationale Measure that may be Necessary for the Preservation or Recovery of our Rights and Liberties as Englishmen and Christians; and we trust in God That, should the State of Our Affairs require it, We shall be ready to Sacrifice our Estates and everything dear in Life, Yea and Life itself, in support of the common Cause."

Upon completion, the Town of Lexington with a unanimous vote adopted the resolves. Immediately afterwards, an additional resolve was passed, warning the residents "That if any Head of a Family in this Town, or any Person, shall from this time forward; & until the Duty taken off, purchase any Tea, Use or consume any Tea in their Famelies [sic], such person shall be looked upon as an Enemy to this town & to this Country, and shall by this Town be treated with Neglect & Contempt."

That evening, the residents of Lexington gathered all tea supplies and burned them. According to the December 16, 1773 edition of the Massachusetts Spy "We are positively informed that the patriotic inhabitants of Lexington unanimously resolved against against the use of Bohea tea of all sorts, Dutch or English importation; and to manifest the sincerity of their resolution, they brought together every ounce contained in the town, and committed it to one common bonfire."

Sunday, December 8, 2019

Sunday, November 17, 2019

Milk Punches and Dragoons - Three Historical Punch Recipes for the Season!

With Christmas 2023 literally right around the corner, the Nerds thought it would be an appropriate time to introduce a trio of historical brandy and rum-based punch recipes from the late 18th and early 19th Centuries for your enjoyment.

Without further hesitation, here are three recipes for the Winter seasons!!

Clarified Milk Punch (18th Century)

Ingredients

8 lemons

1 pineapple

1 pound sugar

2 cinnamon sticks

6 cloves

20 coriander seeds

1-ounce Peychaudís bitters

2 ounces absinthe

1 cup arrack

2 1/2 cups rum

2 1/2 cups cognac

2 1/2 cups brewed green or black tea

2 cups boiling water

5 cups whole milk

Instructions

Zest the lemons (removing only the yellow part of the peel) and juice them. Peel and cut pineapple into large chunks. Put them in a large bowl. Coarsely grind the cinnamon, clove, and coriander seeds into the bowl. Add the lemon peels, lemon juice, pineapple chunks, ground spices, and sugar. Muddle the mixture using a potato masher or large fork.

Add the bitters, absinthe, arrack, cognac, and rum. Stir to combine. Add the green tea and boiling water. Cover and let sit overnight in the refrigerator to infuse the flavors.

Once infused, strain the mixture into a pitcher or other vessel. Discard the solids.

In a medium saucepan, bring the milk to a boil. Once boiling, remove from the heat and add to the strained mixture. The milk will begin to curdle. Gently stir to combine.

Slowly strain the mixture through a cheesecloth-lined strainer. Repeat straining two or three times. You want a clear liquid.

Serve immediately or store the clarified punch in a sterilized glass bottle in the refrigerator for up to 6 months.

To serve, pour 3 ounces of milk punch over a large ice cube and garnish with a lemon peel and freshly grated nutmeg.

Charleston Light Dragoon Punch (Late 18th Century)

Ingredients

4 quarts of black tea

4 cups sugar

1 quart and one cup of lemon juice

1-quart dark rum (Jamaican)

4 quarts California Brandy (any non-gourmet brandy)

½ pint peach (or apricot) brandy

Equal parts Club soda

Instructions

Make the mixture of black tea/lemon juice, stirring in sugar when hot. Add the alcohol. Set aside or bottle for later use.

Place blocks of ice and garnishes of lemon and orange peels in a punch bowl. Pour in equal parts of the tea-brandy-rum mixture with club soda.

In the tradition of our favorite bad-ass smuggler, Sarah Smith Emory of Newburyport, we hope your next social gathering will include “case bottles replenished with choice liquors, and a good supply of New England rum provided for the refreshment of the more humble class of visitors.”

Without further hesitation, here are three recipes for the Winter seasons!!

Clarified Milk Punch (18th Century)

Ingredients

8 lemons

1 pineapple

1 pound sugar

2 cinnamon sticks

6 cloves

20 coriander seeds

1-ounce Peychaudís bitters

2 ounces absinthe

1 cup arrack

2 1/2 cups rum

2 1/2 cups cognac

2 1/2 cups brewed green or black tea

2 cups boiling water

5 cups whole milk

Instructions

Zest the lemons (removing only the yellow part of the peel) and juice them. Peel and cut pineapple into large chunks. Put them in a large bowl. Coarsely grind the cinnamon, clove, and coriander seeds into the bowl. Add the lemon peels, lemon juice, pineapple chunks, ground spices, and sugar. Muddle the mixture using a potato masher or large fork.

Add the bitters, absinthe, arrack, cognac, and rum. Stir to combine. Add the green tea and boiling water. Cover and let sit overnight in the refrigerator to infuse the flavors.

Once infused, strain the mixture into a pitcher or other vessel. Discard the solids.

In a medium saucepan, bring the milk to a boil. Once boiling, remove from the heat and add to the strained mixture. The milk will begin to curdle. Gently stir to combine.

Slowly strain the mixture through a cheesecloth-lined strainer. Repeat straining two or three times. You want a clear liquid.

Serve immediately or store the clarified punch in a sterilized glass bottle in the refrigerator for up to 6 months.

To serve, pour 3 ounces of milk punch over a large ice cube and garnish with a lemon peel and freshly grated nutmeg.

Brandy Milk Punch (Late 18th or Early 19th Century)

Ingredients

2 ounces brandy

1 ounce rum

1 ounce simple syrup

4 ounces milk

Garnish: nutmeg (ground)

Optional: 1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract

Optional: 1 egg white

Instructions

Gather the ingredients.

In a cocktail shaker filled with ice, pour the brandy, rum, simple syrup, milk, optional vanilla extract, and egg white.

Shake well (if you choose to add egg, shake until it hurts).

Strain into an old-fashioned glass with or without crushed ice.

Dust with grated nutmeg for garnish.

Serve and enjoy!

Ingredients

2 ounces brandy

1 ounce rum

1 ounce simple syrup

4 ounces milk

Garnish: nutmeg (ground)

Optional: 1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract

Optional: 1 egg white

Instructions

Gather the ingredients.

In a cocktail shaker filled with ice, pour the brandy, rum, simple syrup, milk, optional vanilla extract, and egg white.

Shake well (if you choose to add egg, shake until it hurts).

Strain into an old-fashioned glass with or without crushed ice.

Dust with grated nutmeg for garnish.

Serve and enjoy!

Charleston Light Dragoon Punch (Late 18th Century)

Ingredients

4 quarts of black tea

4 cups sugar

1 quart and one cup of lemon juice

1-quart dark rum (Jamaican)

4 quarts California Brandy (any non-gourmet brandy)

½ pint peach (or apricot) brandy

Equal parts Club soda

Instructions

Make the mixture of black tea/lemon juice, stirring in sugar when hot. Add the alcohol. Set aside or bottle for later use.

Place blocks of ice and garnishes of lemon and orange peels in a punch bowl. Pour in equal parts of the tea-brandy-rum mixture with club soda.

In the tradition of our favorite bad-ass smuggler, Sarah Smith Emory of Newburyport, we hope your next social gathering will include “case bottles replenished with choice liquors, and a good supply of New England rum provided for the refreshment of the more humble class of visitors.”

Merry Christmas from the Nerds!

Sunday, November 3, 2019

"Retreat! Retreat! Or you all be cutt off!" - The Misfortunes of Colonel Gerrish and the 25th Massachusetts Regiment of the Massachusetts Grand Army

In the days following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the British army found itself trapped; surrounded by an army of Massachusetts Yankees. Unbeknownst to General Gage and his officers, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and the Committee of Safety were confronted with their own dilemma. In the days after April 19th, the provincial forces surrounding Boston began to slowly disappear. At first, militiamen left in small groups, and then by the hundreds, as lack of provisions along with the tug of responsibilities back home weakened their sense of duty. Artemas Ward, the overall commander of the American army besieging Boston, opined that soon he would be the only one left at the siege unless something was done.

To meet this problem, the Provincial Congress agreed to General Ward’s requests that the men be formally enlisted for a given period of time. On April 23, 1775, the legislative body resolved to raise a “Massachusetts Grand Army of 13,600 men and appoint a Committee of Supplies to collect and distribute the necessary commodities.

In accordance with these beating orders, one such regiment raised was Colonel Samuel Gerrish’s Regiment. In exchange for enlistment, each man was paid £5 and promised a bounty of a coat. Designated Colonel Gerrish’s 25th Regiment of the Massachusetts Grand Army, the regiment was composed of 421 men from the Massachusetts towns of Lexington, Woburn, Wenham, Ipswich, Newbury, Manchester, and Rowley and was assigned to the left-wing of the besieging army. Three companies were stationed in Chelsea, two at Sewall’s Point and the remaining three were stationed in Cambridge.

As the weeks passed after the regiment’s formation, the men of the unit quickly discovered that their regiment was plagued with misfortune and mismanagement, both of which were directly attributable to its colonel. Although Gerrish reported his regiment was at full strength on May 19, 1775, the reality was it was only at half strength. Worse, his soldiers were poorly supplied and in desperate need of additional clothing, equipment, and ammunition.

When a militia company from Newbury learned it was to be annexed into the regiment, the men threatened to return home rather than serve under him. On June 2, 1775, six companies petitioned to leave Gerrish’s command and form a new unit under the leadership of Moses Little. Following the submission of the petition, the colonel was notified that “a number of gentlemen have presented a petition to this Congress in behalf of themselves and the men they have enlisted, praying that Captain Moses Little and Mr. Isaac Smith may be appointed and commissioned as two of the field officers over them. Six of said petitioners are returned by you as captains, as appears by your return, and the petition has been committed to a committee, to hear the petitioners and report to the Congress, and it is therefore Ordered that the said Col. Samuel Gerrish be notified, and he is hereby notified, to attend the said committee, at the house of Mr. Learned in Watertown, the 3d day of June instant, at eight o’clock in the forenoon.”

The Committee of Safety conducted a full hearing on the officer’s grievances and permitted the companies to depart and form Little’s Regiment.

On the eve of the Battle of Bunker Hill, Gerrish’s negligent conduct was so commonly known that it became the focus of commentary within several military circles on both sides of the conflict. In a letter to General Gage, Dr. Benjamin Church severely criticized the abilities of the inept colonel.

The regiment first saw combat on June 17, 1775. As the British army advanced on Breed’s Hill General Ward found it impossible to reinforce the American position. The militiamen on Bunker Hill were more than reluctant to join their comrades in the front lines on Breed's Hill; the majority categorically refused to move forward. Most militia companies simply walked away from the fight. An alarmed General Ward correctly surmised that if the desertions continued, not only would the British win the day, but they might sweep away the colonial left flank leaving the way open to an assault on the American headquarters in Cambridge. Ward called upon every available regiment to the fight. Gerrish’s Regiment quickly assembled and marched off towards Charlestown Neck.

The battalion arrived at Charlestown Neck shortly after the first assault on Breed’s Hill and immediately came under heavy fire from the Royal Navy. As the regiment’s major recalled, “[I] went with the recruits and met men from the fort or breastwork where there was a great number of cannon shot struck near me, but they were not suffered to hurt me.” Upon seeing the narrow roadway being raked from both sides by British warships, Colonel Gerrish was overcome with fear. “A tremor seiz’d [Gerrish]. He began to bellow, ‘Retreat! Retreat! Or you all be cutt off!’ which so confused and scar’d our men, that they retreated most precipitately.”

Moments later, Connecticut’s General Israel Putnam arrived on the scene and found Gerrish prostrate on the ground, professing that he was exhausted. The general pleaded with Gerrish to lead his troops onto the field. Finding both the colonel and the entire regiment unresponsive, Putnam resorted to threats and violence. He cursed and threatened the men and even struck some with the flat of his sword in an attempt to drive them forward. Only Christian Febiger, the regimental adjutant, and a handful of men who rallied around him, crossed over the neck, climbed Bunker Hill and moved forward to take up a defensive position on Breed’s Hill. In the midst of the confusion, Thomas Doyle, a private in Captain William Roger’s Company, was killed. The remainder of the regiment scattered and fled back towards Cambridge, where they remained for the rest of the day.

Following the American defeat at Bunker Hill, “a complaint was lodged against [Garish], with Ward, immediately . . . who refused to notice it, on account of the unorganized state of the army.” Years later, General Putnam’s son would bitterly complain about Gerrish’s Regiment, stating “But those that come up as recruits were evidently most terribly frightened, many of them, and did not make up with that true courage that their cause ought to have inspired them with.”

In late July, a British floating battery attacked the American fortifications at Sewall’s Point. Colonel Gerrish, commanding the position, but made no attempt to repel the assault, arguing, “The rascals can do us no harm, and it would be a mere waste of powder to fire at them with our four-pounders.” As evening set in, he ordered the lights of the fortification extinguished. In the darkness, the British continued the bombardment, although the cannonballs flew wide of the fort. For his conduct, Gerrish was immediately arrested. On August 18, 1775, he was tried at Harvard University in the College Chapel for “conduct unworthy of an officer.” The next day he was found guilty.

As a result of the verdict, General George Washington ordered "Col Samuel Garish of the Massachusetts Forces, tried by a General Court Martial of which Brigadier Genl. Green was Presdt. is unanimously found guilty of the Charge exhibited against him, That he behaved unworthy an Officer; that he is guilty of a Breach of the 49th Article of the Rules and Regulations of the Massachusetts Army. The Court therefore sentence and adjudge, the said Col Garish, to be cashiered, and render'd incapable of any employment in the American Army--The General approves the sentence of the Court martial, and orders it to take place immediately."

Surprisingly, many American officers, including the judge advocate presiding over the hearing, declared the punishment was too severe. Following his removal, Gerrish returned to Newbury. Despite his court-martial, the townsmen elected Gerrish to the General Court in 1776.

After Gerrish’s removal, command of the regiment was given to Lieutenant Colonel Loammi Baldwin of Woburn. On April 19th, Baldwin had been one of the first militia officers to bring a force to the aid of Lexington, and to see the bloody results of the engagement on the common. Afterward, he led two hundred Woburn militiamen against the retreating British and devastated their lines at the Bloody Angle in Lincoln. Upon his assuming command in August, the regiment not only experienced a complete reversal from the plague of blunders and mismanagement but quickly developed into a crack fighting unit.

In January 1776 many of the men reenlisted for military service in Baldwin’s successor unit, the 26th Continental Regiment. During that difficult year, Baldwin would lead his regiment across Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. In New York, the regiment fought like wolves to hold off a British amphibious landing at Pelham Bay. The regiment later comprised part of the force that crossed the Delaware River with General Washington on Christmas Night 1776 and routed the Hessian garrison at Trenton. Days later, an advance party of the regiment was given the honor of leading the march to Princeton.

To meet this problem, the Provincial Congress agreed to General Ward’s requests that the men be formally enlisted for a given period of time. On April 23, 1775, the legislative body resolved to raise a “Massachusetts Grand Army of 13,600 men and appoint a Committee of Supplies to collect and distribute the necessary commodities.

In accordance with these beating orders, one such regiment raised was Colonel Samuel Gerrish’s Regiment. In exchange for enlistment, each man was paid £5 and promised a bounty of a coat. Designated Colonel Gerrish’s 25th Regiment of the Massachusetts Grand Army, the regiment was composed of 421 men from the Massachusetts towns of Lexington, Woburn, Wenham, Ipswich, Newbury, Manchester, and Rowley and was assigned to the left-wing of the besieging army. Three companies were stationed in Chelsea, two at Sewall’s Point and the remaining three were stationed in Cambridge.

|

| A map showing Boston and vicinity, including Bunker Hill, Dorchester Heights, and the troop disposition of Gen. Artemas Ward during the Siege of Boston. From "Marshall's Life of Washington" (1806) |

As the weeks passed after the regiment’s formation, the men of the unit quickly discovered that their regiment was plagued with misfortune and mismanagement, both of which were directly attributable to its colonel. Although Gerrish reported his regiment was at full strength on May 19, 1775, the reality was it was only at half strength. Worse, his soldiers were poorly supplied and in desperate need of additional clothing, equipment, and ammunition.

When a militia company from Newbury learned it was to be annexed into the regiment, the men threatened to return home rather than serve under him. On June 2, 1775, six companies petitioned to leave Gerrish’s command and form a new unit under the leadership of Moses Little. Following the submission of the petition, the colonel was notified that “a number of gentlemen have presented a petition to this Congress in behalf of themselves and the men they have enlisted, praying that Captain Moses Little and Mr. Isaac Smith may be appointed and commissioned as two of the field officers over them. Six of said petitioners are returned by you as captains, as appears by your return, and the petition has been committed to a committee, to hear the petitioners and report to the Congress, and it is therefore Ordered that the said Col. Samuel Gerrish be notified, and he is hereby notified, to attend the said committee, at the house of Mr. Learned in Watertown, the 3d day of June instant, at eight o’clock in the forenoon.”

The Committee of Safety conducted a full hearing on the officer’s grievances and permitted the companies to depart and form Little’s Regiment.

On the eve of the Battle of Bunker Hill, Gerrish’s negligent conduct was so commonly known that it became the focus of commentary within several military circles on both sides of the conflict. In a letter to General Gage, Dr. Benjamin Church severely criticized the abilities of the inept colonel.

The regiment first saw combat on June 17, 1775. As the British army advanced on Breed’s Hill General Ward found it impossible to reinforce the American position. The militiamen on Bunker Hill were more than reluctant to join their comrades in the front lines on Breed's Hill; the majority categorically refused to move forward. Most militia companies simply walked away from the fight. An alarmed General Ward correctly surmised that if the desertions continued, not only would the British win the day, but they might sweep away the colonial left flank leaving the way open to an assault on the American headquarters in Cambridge. Ward called upon every available regiment to the fight. Gerrish’s Regiment quickly assembled and marched off towards Charlestown Neck.

The battalion arrived at Charlestown Neck shortly after the first assault on Breed’s Hill and immediately came under heavy fire from the Royal Navy. As the regiment’s major recalled, “[I] went with the recruits and met men from the fort or breastwork where there was a great number of cannon shot struck near me, but they were not suffered to hurt me.” Upon seeing the narrow roadway being raked from both sides by British warships, Colonel Gerrish was overcome with fear. “A tremor seiz’d [Gerrish]. He began to bellow, ‘Retreat! Retreat! Or you all be cutt off!’ which so confused and scar’d our men, that they retreated most precipitately.”

|

| Don Troiani's "Bunker Hill". |

Moments later, Connecticut’s General Israel Putnam arrived on the scene and found Gerrish prostrate on the ground, professing that he was exhausted. The general pleaded with Gerrish to lead his troops onto the field. Finding both the colonel and the entire regiment unresponsive, Putnam resorted to threats and violence. He cursed and threatened the men and even struck some with the flat of his sword in an attempt to drive them forward. Only Christian Febiger, the regimental adjutant, and a handful of men who rallied around him, crossed over the neck, climbed Bunker Hill and moved forward to take up a defensive position on Breed’s Hill. In the midst of the confusion, Thomas Doyle, a private in Captain William Roger’s Company, was killed. The remainder of the regiment scattered and fled back towards Cambridge, where they remained for the rest of the day.

Following the American defeat at Bunker Hill, “a complaint was lodged against [Garish], with Ward, immediately . . . who refused to notice it, on account of the unorganized state of the army.” Years later, General Putnam’s son would bitterly complain about Gerrish’s Regiment, stating “But those that come up as recruits were evidently most terribly frightened, many of them, and did not make up with that true courage that their cause ought to have inspired them with.”

In late July, a British floating battery attacked the American fortifications at Sewall’s Point. Colonel Gerrish, commanding the position, but made no attempt to repel the assault, arguing, “The rascals can do us no harm, and it would be a mere waste of powder to fire at them with our four-pounders.” As evening set in, he ordered the lights of the fortification extinguished. In the darkness, the British continued the bombardment, although the cannonballs flew wide of the fort. For his conduct, Gerrish was immediately arrested. On August 18, 1775, he was tried at Harvard University in the College Chapel for “conduct unworthy of an officer.” The next day he was found guilty.

As a result of the verdict, General George Washington ordered "Col Samuel Garish of the Massachusetts Forces, tried by a General Court Martial of which Brigadier Genl. Green was Presdt. is unanimously found guilty of the Charge exhibited against him, That he behaved unworthy an Officer; that he is guilty of a Breach of the 49th Article of the Rules and Regulations of the Massachusetts Army. The Court therefore sentence and adjudge, the said Col Garish, to be cashiered, and render'd incapable of any employment in the American Army--The General approves the sentence of the Court martial, and orders it to take place immediately."

Surprisingly, many American officers, including the judge advocate presiding over the hearing, declared the punishment was too severe. Following his removal, Gerrish returned to Newbury. Despite his court-martial, the townsmen elected Gerrish to the General Court in 1776.

After Gerrish’s removal, command of the regiment was given to Lieutenant Colonel Loammi Baldwin of Woburn. On April 19th, Baldwin had been one of the first militia officers to bring a force to the aid of Lexington, and to see the bloody results of the engagement on the common. Afterward, he led two hundred Woburn militiamen against the retreating British and devastated their lines at the Bloody Angle in Lincoln. Upon his assuming command in August, the regiment not only experienced a complete reversal from the plague of blunders and mismanagement but quickly developed into a crack fighting unit.

In January 1776 many of the men reenlisted for military service in Baldwin’s successor unit, the 26th Continental Regiment. During that difficult year, Baldwin would lead his regiment across Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. In New York, the regiment fought like wolves to hold off a British amphibious landing at Pelham Bay. The regiment later comprised part of the force that crossed the Delaware River with General Washington on Christmas Night 1776 and routed the Hessian garrison at Trenton. Days later, an advance party of the regiment was given the honor of leading the march to Princeton.

Sunday, September 15, 2019

"Fall Down and Worship Our Sovereign Lord the Mob" - Massachusetts Mob Violence on the Eve of the American Revolution

A couple of weekends ago, the Nerds were at the Newport Historical Society for the reenactment of the 1769 burning of the HMS Liberty. On July 19, 1769, the crew of the Liberty accosted Connecticut ship captain Joseph Packwood, seized two ships and towed the vessels into Newport. In retribution, Captain Packwood and a mob of Rhode Islanders confronted the Liberty’s Captain and then boarded, scuttled, and later burned the Royal Navy sloop on the north end of Goat Island, located in Newport Harbor.

While at the reenactment, we had a lively discussion with several reenactors about the use of mob violence as a method of protesting unpopular political policies and beliefs throughout American history.

Even the most casual student of Revolutionary War history knows that the American colonies had its fair share of violent protests against British governmental policies. Of course, Massachusetts mob violence started in the mid 1760s when the Sugar and Stamp acts brought on an explosion of riots, boycotts and protests.

In Haverhill, Richard Saltonstall fared slightly better. A mob from Haverhill and neighboring Salem, New Hampshire gathered, armed themselves with clubs and descended upon his mansion. Saltonstall quickly came to the door and met the crowd. According to one 19th Century account, he asserted that as Sheriff of Essex County he was bound by an oath of allegiance to the king and was obligated to carry out the duties of the office, including supporting the Stamp Act. Saltonstall allegedly warned the crowd that they were not pursuing a wise or prudent course by threatening him with violence. However, to diffuse the tense situation, Saltonstall then invited the mob to a nearby “tavern and call for entertainment at his expense. They then huzzard to the praise of Colonel Saltonstall."

Three years later, Boston mobs were once again protesting economic policies through the use of violence and the threat of violence.

That evening, Bostonians began to badger and taunt a lone British sentry on guard duty in front of the Royal Custom House. When the crowd began to pelt him with snowballs and ice, he called for help and was reinforced by a squad of soldiers from the 29th Regiment of Foot. When the crowd pressed closer, the nervous regulars opened fire. Five men in the crowd were killed and a number of others were wounded.

For the next two years, tensions seemed to lessen in the colonies, particularly Massachusetts. However, when Parliament attempted to control provincial judges in 1772 by directly controlling their salaries, Massachusetts once again responded in opposition and protest.

Of course, mob violence of the 1760s and 1770s had a dual result. On the one hand, the riots and violence did contribute in some part to government officials abandoning or limiting unpopular laws in the American colonies. On the other hand, the mob violence drove many of those colonists who wished to remain neutral squarely into what would become the loyalist camp.

While at the reenactment, we had a lively discussion with several reenactors about the use of mob violence as a method of protesting unpopular political policies and beliefs throughout American history.

Even the most casual student of Revolutionary War history knows that the American colonies had its fair share of violent protests against British governmental policies. Of course, Massachusetts mob violence started in the mid 1760s when the Sugar and Stamp acts brought on an explosion of riots, boycotts and protests.

At first, Massachusetts’ response to the acts were peaceful, with the inhabitants merely boycotting certain goods. However, resistance to the taxes soon became violent. Under the guidance of Samuel Adams, Bostonians began a campaign of terror directed against those who supported the Stamp Act. It began on August 14, 1765 with an effigy of Andrew Oliver, the appointed stamp distributor for Massachusetts, being hung from a “liberty tree” in plain view by the “sons of liberty.” That evening, the Oliver’s luxurious home was burned to the ground. A chastened Oliver quickly resigned his commission.

The following evening, incited by a rumor that he supported the Stamp Act, the home of Thomas Hutchinson, Lieutenant Governor of the colony, was surrounded by an unruly mob. When Hutchinson refused to accede to the demand that he come out and explain his position, the crowd broke several windows and then dispersed. Two weeks later, on August 28, 1765, an even larger mob assembled and descended upon the homes of several individuals suspected of favoring the Stamp Act, including again that of the Lieutenant Governor.

Hutchinson managed to evacuate his family to safety before the mob arrived. Then, as the Lieutenant Governor later described it, “the hellish crew fell upon my house with the rage of divels and in a moment with axes split down the door and entered. My son heard them cry ‘damn him he is upstairs we’ll have him.’ Some ran immediately as high as the top of the house, others filled the rooms below and cellars and others remained without the house to be employed there. I was obliged to retire thro yards and gardens to a house more remote where I remained until 4 o’clock by which time one of the best finished houses in the Province had nothing remaining but the bare walls and floors.”

Meanwhile in Newburyport, Newburyport officials declared “the late act of parliament is very grievous, and that this town as much as in them lies endeavour the repeal of the same in all lawful ways, and that it is the desire of the town that no man in it will accept of the office of distributing the stampt papers, as he regards the displeasure of the town and that they will deem the person accepting of such office an enemy to his country.” When an unknown Newburyport resident disregarded the town’s warning and accepted an appointment as a “stamp distributor”, an angry mob quickly mobilized.

According to Newburyport resident Joshua Coffin, the crowd immediately started a campaign of intimidation against the stamp distributor. “In Newburyport, the effigy a Mr. I— B—, who had accepted the office of stamp distributor, was suspended, September twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth, from a large elm tree which stood in Mr. Jonathan Greenleaf's yard, at the foot of King street, [now Federal street], a collection of tar barrels set on fire, the rope cut, and the image dropped into the flames. At ten o'clock, P. M., all the bells in town were rung. ‘I am sorry to see that substitute,’ said a distinguished citizen of Newburyport, ‘I wish it had been the original.’”

Not satisfied that their message had been properly conveyed, members of the mob then armed themselves with clubs and patrolled the town questioning strangers and residents alike about their position on the crisis. “Companies of men, armed with clubs, were accustomed to parade the streets of Newbury and Newburyport, at night, and, to every man they met, put the laconic question, “stamp or no stamp”. The consequences of an affirmative reply, were anything but pleasant.”

As Coffin noted, when one stranger was unable to answer the mob’s questions, they beat him severely. “In one instance, a stranger, having arrived in town, was seized by the mob, at the foot of Green street, and, not knowing what answer to make to the question, stood mute. As the mob allow no neutrals, and as silence with them is a crime, he was severely beaten.” A second man fared better when he was able to provide a clever answer. “The same question was put to another stranger, who replied, with a sagacity worthy of a vicar of Bray, or a Talleyrand, ‘I am as you are.’ He was immediately cheered and applauded, as a true son of liberty, and permitted to depart in peace, wondering, no doubt, at his own sudden popularity.”

Meanwhile in Newburyport, Newburyport officials declared “the late act of parliament is very grievous, and that this town as much as in them lies endeavour the repeal of the same in all lawful ways, and that it is the desire of the town that no man in it will accept of the office of distributing the stampt papers, as he regards the displeasure of the town and that they will deem the person accepting of such office an enemy to his country.” When an unknown Newburyport resident disregarded the town’s warning and accepted an appointment as a “stamp distributor”, an angry mob quickly mobilized.

According to Newburyport resident Joshua Coffin, the crowd immediately started a campaign of intimidation against the stamp distributor. “In Newburyport, the effigy a Mr. I— B—, who had accepted the office of stamp distributor, was suspended, September twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth, from a large elm tree which stood in Mr. Jonathan Greenleaf's yard, at the foot of King street, [now Federal street], a collection of tar barrels set on fire, the rope cut, and the image dropped into the flames. At ten o'clock, P. M., all the bells in town were rung. ‘I am sorry to see that substitute,’ said a distinguished citizen of Newburyport, ‘I wish it had been the original.’”

Not satisfied that their message had been properly conveyed, members of the mob then armed themselves with clubs and patrolled the town questioning strangers and residents alike about their position on the crisis. “Companies of men, armed with clubs, were accustomed to parade the streets of Newbury and Newburyport, at night, and, to every man they met, put the laconic question, “stamp or no stamp”. The consequences of an affirmative reply, were anything but pleasant.”

As Coffin noted, when one stranger was unable to answer the mob’s questions, they beat him severely. “In one instance, a stranger, having arrived in town, was seized by the mob, at the foot of Green street, and, not knowing what answer to make to the question, stood mute. As the mob allow no neutrals, and as silence with them is a crime, he was severely beaten.” A second man fared better when he was able to provide a clever answer. “The same question was put to another stranger, who replied, with a sagacity worthy of a vicar of Bray, or a Talleyrand, ‘I am as you are.’ He was immediately cheered and applauded, as a true son of liberty, and permitted to depart in peace, wondering, no doubt, at his own sudden popularity.”

In Haverhill, Richard Saltonstall fared slightly better. A mob from Haverhill and neighboring Salem, New Hampshire gathered, armed themselves with clubs and descended upon his mansion. Saltonstall quickly came to the door and met the crowd. According to one 19th Century account, he asserted that as Sheriff of Essex County he was bound by an oath of allegiance to the king and was obligated to carry out the duties of the office, including supporting the Stamp Act. Saltonstall allegedly warned the crowd that they were not pursuing a wise or prudent course by threatening him with violence. However, to diffuse the tense situation, Saltonstall then invited the mob to a nearby “tavern and call for entertainment at his expense. They then huzzard to the praise of Colonel Saltonstall."

Three years later, Boston mobs were once again protesting economic policies through the use of violence and the threat of violence.

In March, 1768 rioters went to “Commissioner Burch’s home and with clubs assembled before his door a great part of the evening, and he was obliged to send away his wife and children by a back door.” Inspector William Woolton returned home one evening to find “4 men passing him, one with a stick or bludgeon in his hand accosted him saying, ‘Damn your Blood we will be at you to Morrow night.’ ”

In Salem, Massachusetts, a government informant who assisted in the enforcement of the Townshend Acts was discovered and quickly seized by an angry mob. Afterwards, "his Head, Body and Limbs were covered with warm Tar and then a large quantity of Feathers were applied to all Parts, which by closely adhering to the Tar, Exhibited an odd figure, the Drollery of which can easily be imagined." He was set in a cart with the placard "Informer on his breast and back and escorted out of town" by the mob, who warned him of worse treatment if he returned.

On September 10, 1768 a large Newburyport mob armed themselves with clubs and began to search for the two men they believed were local informants. According to the September 27th edition of the Essex Gazette, one Joshua Vickery was quickly found and "in a riotous manner asaulted in the Kings Highway in Newbury-Port, seized and carried by Force to the public stocks in the said Town, where he sat from three to five o'clock, in the afternoon, most of the Time on the sharpest stone that could be found, which put him to extreme Pain, so that he once fainted."

When he regained consciousness, Vickery was "taken out of the Stocks, put into a cart and carried thro' the Town with a Rope about his Neck, his Hands tied behind him until the Dusk of the Evening, during which time he was severely pelted with Eggs, Gravel and Stones, and was much wounded thereby; he was then taken out of the Cart, carried into a dark Ware-houfe, and hand-cuffed with Irons, without Bed or Cloathing, and in a Room where he could not lay strait, but made the Edge of a Tar Pot serve for a Pillow, so that when he arofe the Hair was tore from his Head."

Vickery spent the next day (Sunday) under guard in the warehouse. Several of his friends attempted to visit the carpenter, only to be rebuffed by the mob. Only his wife, "who with Difficulty obtained Liberty to speak to him" was granted access.

On Monday, September 12th, Vickery was dragged out of the warehouse and subjected to intense questioning. Surprisingly, he was able to convince mob leaders "that he never did, directly or indirectly, make or give Information to any Officer of the Customs, nor to any other Person, either against Cap' John Emmery or any other man whomsoever."

A second suspected informant "was stripped naked, tarred and then Committed to Gaol for Breach of the Peace” by the Newburyport mob.

On March 5, 1770, the violent protests culminated with the Boston Massacre. As loyalist James Chalmers later noted “March 5, 1770 is a day when the rebellious citizens of the Boston Colony demonstrated their commitment to mob violence, and their willingness to be led down the path to destruction by a few evil men . . . Soldiers, at their duty posts, minding their own business and acting non-confrontational, were verbally assaulted by Bostonian men with epitaphs of ‘bloody back’, ‘lousy rascal’, ‘dammed rascally scoundrel’, and ‘lobster son of a b----’. Physical violence was done to the soldiers, unprovoked, by the mob pelting the soldiers with snowballs, icicles, and pieces of wood . . . It is clear to us that this whole series of events could have been prevented if the small band of inciters did not lure the unsuspecting civilians to perform the aggressive acts perpetrated.”

In Salem, Massachusetts, a government informant who assisted in the enforcement of the Townshend Acts was discovered and quickly seized by an angry mob. Afterwards, "his Head, Body and Limbs were covered with warm Tar and then a large quantity of Feathers were applied to all Parts, which by closely adhering to the Tar, Exhibited an odd figure, the Drollery of which can easily be imagined." He was set in a cart with the placard "Informer on his breast and back and escorted out of town" by the mob, who warned him of worse treatment if he returned.

On September 10, 1768 a large Newburyport mob armed themselves with clubs and began to search for the two men they believed were local informants. According to the September 27th edition of the Essex Gazette, one Joshua Vickery was quickly found and "in a riotous manner asaulted in the Kings Highway in Newbury-Port, seized and carried by Force to the public stocks in the said Town, where he sat from three to five o'clock, in the afternoon, most of the Time on the sharpest stone that could be found, which put him to extreme Pain, so that he once fainted."

When he regained consciousness, Vickery was "taken out of the Stocks, put into a cart and carried thro' the Town with a Rope about his Neck, his Hands tied behind him until the Dusk of the Evening, during which time he was severely pelted with Eggs, Gravel and Stones, and was much wounded thereby; he was then taken out of the Cart, carried into a dark Ware-houfe, and hand-cuffed with Irons, without Bed or Cloathing, and in a Room where he could not lay strait, but made the Edge of a Tar Pot serve for a Pillow, so that when he arofe the Hair was tore from his Head."

Vickery spent the next day (Sunday) under guard in the warehouse. Several of his friends attempted to visit the carpenter, only to be rebuffed by the mob. Only his wife, "who with Difficulty obtained Liberty to speak to him" was granted access.

On Monday, September 12th, Vickery was dragged out of the warehouse and subjected to intense questioning. Surprisingly, he was able to convince mob leaders "that he never did, directly or indirectly, make or give Information to any Officer of the Customs, nor to any other Person, either against Cap' John Emmery or any other man whomsoever."

A second suspected informant "was stripped naked, tarred and then Committed to Gaol for Breach of the Peace” by the Newburyport mob.

On March 5, 1770, the violent protests culminated with the Boston Massacre. As loyalist James Chalmers later noted “March 5, 1770 is a day when the rebellious citizens of the Boston Colony demonstrated their commitment to mob violence, and their willingness to be led down the path to destruction by a few evil men . . . Soldiers, at their duty posts, minding their own business and acting non-confrontational, were verbally assaulted by Bostonian men with epitaphs of ‘bloody back’, ‘lousy rascal’, ‘dammed rascally scoundrel’, and ‘lobster son of a b----’. Physical violence was done to the soldiers, unprovoked, by the mob pelting the soldiers with snowballs, icicles, and pieces of wood . . . It is clear to us that this whole series of events could have been prevented if the small band of inciters did not lure the unsuspecting civilians to perform the aggressive acts perpetrated.”

That evening, Bostonians began to badger and taunt a lone British sentry on guard duty in front of the Royal Custom House. When the crowd began to pelt him with snowballs and ice, he called for help and was reinforced by a squad of soldiers from the 29th Regiment of Foot. When the crowd pressed closer, the nervous regulars opened fire. Five men in the crowd were killed and a number of others were wounded.

For the next two years, tensions seemed to lessen in the colonies, particularly Massachusetts. However, when Parliament attempted to control provincial judges in 1772 by directly controlling their salaries, Massachusetts once again responded in opposition and protest.

Of course, mob violence of the 1760s and 1770s had a dual result. On the one hand, the riots and violence did contribute in some part to government officials abandoning or limiting unpopular laws in the American colonies. On the other hand, the mob violence drove many of those colonists who wished to remain neutral squarely into what would become the loyalist camp.

As mob violence continued in pre Revolutionary War Massachusetts, many colonists attempted to remain neutral. However, such a political stance became impossible. Dr. William Paine of Worcester gave up his neutrality and declared himself a loyalist after he experienced "too many abuses" and "insults" from Patriots. Samuel Curwen, Judge of the Admiralty, complained Whig “tempers get more and more soured and malevolent against all moderate men, whom they see fit to reproach as enemies of their country by the name of Tories, among whom I am unhappily (although unjustly) ranked.” One minister lashed out at the patriot mobs who routinely and illegally entered and searched the homes of their political opponents. “Do as you please: If you like it better, choose your Committee, or suffer it to be Chosen by half a dozen Fools in your neighborhood – open your doors to them let them examine your tea canisters, and molasses-jugs, and your wives and daughters pettycoats – bow and cringe and tremble and quake – fall down and worship our sovereign Lord the Mob.”

Sunday, August 25, 2019

"Fortified In Such a Manner As To Do Honour" - The Impregnable Newburyport Harbor

Recently, the Nerds have been researching why the coastal community of Newburyport quickly became a safe haven for Massachusetts and New Hampshire vessels during the American Revolution. As early as mid-summer 1775, the Newburyport Committee of Safety reported to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress “that the Harbour of this Town … is already become an Assylum for many Vessells, who seek to avoid the Piratical Ships of our Enemies: Yet as there are many small armed Vessells, which are cruising along all the shores of the Province, & frequently crossing this Bay: many Vessells some loaded with Provissions, & some with Fuel & Lumber, have been taken before they coud reach the Mouth of this Harbour, & sent to Boston.”

So why were privateers, merchant vessels and supply ships often fleeing to this particular town? Simply put, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Newburyport turned itself and the Merrimack River into an impregnable fortress. Recent research has revealed that Newburyport, in conjunction with the towns of Amesbury, Salisbury and Newbury created an early warning network and at least three defensive lines that included coastal fortifications, physical obstructions, floating batteries, interior redoubts and two companies of militia that were on a constant state of alert. In short, the coastal town offered extensive protection from His Majesty’s navy.

It appears two possible events triggered the move to fortify the Merrimack River in 1775. The first was the Ipswich Fright which occured in the days after Lexington and Concord. This particular event was the result of a false rumor that British soldiers had landed in Ipswich and had killed the local populace. As the rumor spread, widespread panic set in among the residents of several North Shore Massachusetts towns and many, including those from Newburyport, fled to New Hampshire.

So why were privateers, merchant vessels and supply ships often fleeing to this particular town? Simply put, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Newburyport turned itself and the Merrimack River into an impregnable fortress. Recent research has revealed that Newburyport, in conjunction with the towns of Amesbury, Salisbury and Newbury created an early warning network and at least three defensive lines that included coastal fortifications, physical obstructions, floating batteries, interior redoubts and two companies of militia that were on a constant state of alert. In short, the coastal town offered extensive protection from His Majesty’s navy.

It appears two possible events triggered the move to fortify the Merrimack River in 1775. The first was the Ipswich Fright which occured in the days after Lexington and Concord. This particular event was the result of a false rumor that British soldiers had landed in Ipswich and had killed the local populace. As the rumor spread, widespread panic set in among the residents of several North Shore Massachusetts towns and many, including those from Newburyport, fled to New Hampshire.

The second event transpired the following month when a detachment of British sailors and officers from the HMS Scarborough entered Newburyport Harbor under the cover of darkness to scout the town’s defensive capabilities. According to the Essex Journal, “last Tuesday evening (May 23) a barge belonging to the man of war lying at Portsmouth, rowing up and down the river to make discoveries with two small officers and six seamen.” Unfortunately, the mission was an utter failure as the “tars not liking the employ, tied their commanders, then run the boat ashore, and were so impolite as to wish the prisoners good night, and came off.” Upon entering Newburyport, the deserters alerted the town of the mission and the location of the officers. However, “the officers soon got loose and rowed themselves back to the ship” before they were apprehended.

The two events rattled Newburyport. Many residents realized that if a Royal Navy warship entered the Merrimack, it could easily sail down the river and not only bombard the town, wharves and shipyards, but it could also raze Salisbury and Amesbury. As a result, officials from the three towns and Newbury agreed that the mouth or the river, as well as the harbor itself, needed to be fortified.

The first step the locals took to protect the harbor was to place an obstruction at the mouth of the Merrimack. Local lore suggests that a pair of ships were sunk to block the river entrance. However, two period accounts reveal that it was actually piers that were sunk. According to a 1785 request for compensation from the citizens of Newburyport to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, “the said town in order to guard and defend themselves and the neighbouring towns from the apprehended invasions and attacks of the enemy then infesting the sea. coasts, and making depredations on the maritime towns of the state, prepared and sunk a number of piers in the channel of Merrimac river, near the mouth thereo.” A second description noted that the obstruction included a narrow passageway for friendly vessels and that a nearby raft could be submerged into the opening to close off the river if an enemy vessel approached. As loyalist Stephen Kemble described, “all the Vessels from Cape Ann are in the (Merrimack) River, and the mouth of it shut up by driving Piles or Stakes into the Bottom, except a small passage, which is Ieft open for Vessels, where a Raft is moored, to be sunk occasionally.”

Shortly after blocking the river, the towns of Salisbury and Amesbury began to build a coastal fortification on Salisbury Point, which was located near the river entrance. Known as Fort Nichol, this earthwork was a nine gun battery that was manned by militiamen from the two towns. Across the river on Plum Island, the towns of Newbury and Newburyport agreed to construct their own coastal fortification. “We are now about erecting a small Battery or Breast-Work with 3 or 4 heavier Cannon which can be procurd, to defend ourselves against any Attacks by Water.” When the redoubt was completed, it was named Fort Faith and was manned by militiamen from Newbury and Newburyport.

As an aside, iIn addition to receiving wages, the men stationed at Fort Faith were also provided with “candles and sweetening for their beer.”

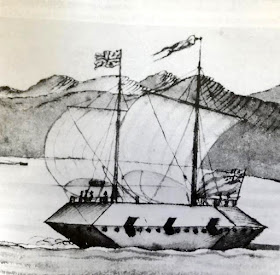

Behind the two forts and sunken piers was a second line of defense. At some point in 1775, the residents of Newburyport constructed and launched a floating battery. A floating battery was a watercraft that carried heavy armaments but carried little else to qualify as a war ship. According to a period account, Newburyport “constructed a floating battery, built a barge and made a number of gun carriages.”

The two events rattled Newburyport. Many residents realized that if a Royal Navy warship entered the Merrimack, it could easily sail down the river and not only bombard the town, wharves and shipyards, but it could also raze Salisbury and Amesbury. As a result, officials from the three towns and Newbury agreed that the mouth or the river, as well as the harbor itself, needed to be fortified.

The first step the locals took to protect the harbor was to place an obstruction at the mouth of the Merrimack. Local lore suggests that a pair of ships were sunk to block the river entrance. However, two period accounts reveal that it was actually piers that were sunk. According to a 1785 request for compensation from the citizens of Newburyport to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, “the said town in order to guard and defend themselves and the neighbouring towns from the apprehended invasions and attacks of the enemy then infesting the sea. coasts, and making depredations on the maritime towns of the state, prepared and sunk a number of piers in the channel of Merrimac river, near the mouth thereo.” A second description noted that the obstruction included a narrow passageway for friendly vessels and that a nearby raft could be submerged into the opening to close off the river if an enemy vessel approached. As loyalist Stephen Kemble described, “all the Vessels from Cape Ann are in the (Merrimack) River, and the mouth of it shut up by driving Piles or Stakes into the Bottom, except a small passage, which is Ieft open for Vessels, where a Raft is moored, to be sunk occasionally.”

Shortly after blocking the river, the towns of Salisbury and Amesbury began to build a coastal fortification on Salisbury Point, which was located near the river entrance. Known as Fort Nichol, this earthwork was a nine gun battery that was manned by militiamen from the two towns. Across the river on Plum Island, the towns of Newbury and Newburyport agreed to construct their own coastal fortification. “We are now about erecting a small Battery or Breast-Work with 3 or 4 heavier Cannon which can be procurd, to defend ourselves against any Attacks by Water.” When the redoubt was completed, it was named Fort Faith and was manned by militiamen from Newbury and Newburyport.

As an aside, iIn addition to receiving wages, the men stationed at Fort Faith were also provided with “candles and sweetening for their beer.”

Behind the two forts and sunken piers was a second line of defense. At some point in 1775, the residents of Newburyport constructed and launched a floating battery. A floating battery was a watercraft that carried heavy armaments but carried little else to qualify as a war ship. According to a period account, Newburyport “constructed a floating battery, built a barge and made a number of gun carriages.”

|

| Image of a British floating battery. From “A North View of Crown Point” by Thomas Davies, c. 1759 (Library of Congress) |

There is some evidence that there may have been a third defensive line of redoubts on Coffin Point in Salisbury and near the Joppa Flats in Newburyport. Strategically, both locations would be ideal for the placement of batteries as the Merrimack River narrows between those two points.

Finally, Newburyport had several militia companies stationed inside the town, of which two were in a constant state of readiness. “There are now in the pay of the Government, two Companies stationed in the (town of) Newbury Port, out of which Companies, it is probable, a large Part of the necessary Complement wou'd readily engage.”

Massachusetts officials who inspected Newburyport’s defensive works in 1776 were impressed with what they saw. As one official noted “The Town of Newbury Port is fortified in such a Manner as to do Honour to the gentlemen concerned. The Noble Exertions that have been made by that Town for the Defence of such an important Port of the Colony demands the most grateful Returns from every Well Wisher to American Liberty.”

In total, at least twenty artillery pieces of various sizes, including “ten nine pounders, 8 sixes and two fours”, protected Newburyport Harbor.

Of course, the importance of Newburyport did not go unnoticed by British military leaders. As early as June 15, 1775, General Thomas Gage reported to Admiral Samuel Graves that a “Mr [Benjamin] Hallowell informed me this Morning that the Rebels have Vessels out watching for the Trade bound to Marblehead and Salem, and to give them notice to put into Newbury Port in Order to avoid your Ships.” Later that same day, the admiral notified his officers about the significance of Newburyport. “In consequence of intelligence this day the Admiral acquainted the Commanders of the cruizing Vessels that the Rebels had fishing Boats, out watching for their homeward bound Trade to direct them to avoid our Cruizers by going for Newbury Port.”

The Royal Navy often probed the outer defensive works and would pursue privateers, merchant vessels and American supply ships right up "to the mouth of the river” to test the harbor’s outer defenses.

In August 1775, the commanding officer of the Scarborough, then anchored off the coast of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, recommended that the harbor be breached and Newburyport bombarded. In response, Admiral Graves admitted such an operation was unlikely due to the lack of ships. “I observe what you say about Newbury; that place and all others indeed require to be strictly attended to, but where are the Ships?” Two months later, Admiral Graves ordered Lieutenant Henry Mowat, of the HMS Canceaux to burn Newburyport and other Massachusetts seaports to the ground. Fortunately for Newburyport, Mowat had other plans and attacked Falmouth, Maine instead.

As the war progressed, Newburyport slowly scaled back its harbor defenses. By 1777, many of artillery pieces had been removed and loaned to the Continental Navy. The floating battery was sold in 1778. That same year, a flood washed away part if not most of the sunken piers located at the river entrance. Fort Faith remained in existence until the end of the war when a hurricane destroyed it. Fort Nichol was renamed Fort Merrimac and remained in use until the American Civil War. In 1865, a Nor’easter struck and the redoubt slipped into the ocean.

Thursday, August 8, 2019

"Wath a View to Rescue the Soldier" - Who Was the British Deserter Who Trained the Freetown Militia?

A few years ago, we had discussed British army deserter George Marsden and his role in training minute and militia companies in the Merrimack Valley region of Massachusetts.

As you may recall, Marsden was a grenadier from the 59th Regiment of Foot. He and his regiment arrived in New England in 1768. However, by 1769 the 59th was in Nova Scotia. A muster roll from October 1770 reveals Marsden was promoted to the rank of sergeant. Unfortunately, by 1774 he was demoted back to a private. The reason for the demotion is unknown but the regimental muster rolls indicate that on July 24, 17774 he deserted from his regiment. Afterward, Marsden fled to Haverhill.

Marsden was the logical choice to train the minute companies of Andover, Bradford and Haverhill. He was intelligent and had extensive experience within the British army. In March and April of 1775, the units actively worked with Marsden to prepare for war. Haverhill initially voted that its minute men “be duly disciplined in Squads three half days in a Week, three hours in each half day.” On March 14, 1775, the town also voted to raise thirty dollars “to procure a military instructor to instruct the Militia in the Art Military.” One week later, it was voted that the minute-men should train one whole day per week, instead of three half days as previously voted. Furthermore, the minutemen were to be trained by a “Mr George Marsden, whom we have hired.”

Interestingly, this is not the only record of a George Marsden being hired to train minute companies in the Merrimack Valley region of Massachusetts. A Haverhill “Independent Corps” commanded by Captain Brickett passed their own resolution “that we hire Mr George Marsdin for 4 days at 12s a day, & that he be paid out of the fines.” Similar records from Andover and Bradford Massachusetts also reference the hiring of George Marsden to train their minute companies.

After we published our findings, J.L. Bell and Don Hagist brought to our attention another British deserter who had been retained by a Rhode Island militia company to train them in the 1764 Crown Manual Exercise. Yesterday we stumbled across a third British deserter who was possibly training a Freetown, Massachusetts militia company.

Col. Thomas Gilbert was a veteran of the French and Indian War and a staunch loyalist. On the eve of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, he recruited over one hundred men, organized them into a military company and secured stands or arms for them. In early April, residents of neighboring towns received reports that Colonel Gilbert had left Freetown and was planning to return with military reinforcements. A preemptive strike was quickly organized by local minute and militia companies.

According to a Providence newspaper, “that on Monday before, parties of Minute men, etc. from every town in that County, with arms and ammunition, met at Freetown that morning in order to take Col. Gilbert, but he had fled on board the Rose, man of war at Newport.” Ezra Stiles noted that “above a Thousd Men assembled in Arms at Freetown to lay Col. Gilbert as they had heard he had risen up against his Country. They came from all parts round as far as Middleboro, Rochester &c. They took about 30 of his Men & disarmed them, tho' they had lately taken the Kings Arms.”

Shortly after the Freetown Raid, some of Gilbert’s men returned to Freetown and captured a British soldier who apparently had been training the local militia in the “Military Exercise”. According to the Reverend Ezra Stiles, “Some of Col. Gilbert's Men it is said seized a Soldier of the Regulars a Deserter who was teaching military Exercise at Freetown, & were about carrying him to Gen. Gage at Boston.”

At this time it is unknown who this soldier was, what unit he deserted from or what his fate was after his abduction. According to Stiles, there was an attempt to rescue him from his kidnappers. “The Night before last 50 Men marched from Dartmouth to joyn a large Body wath a View to rescue the Soldier.” Whether or not the rescue effort succeeded remains a mystery. Of course, if the deserter was successfully transported to Boston, we’re curious about whether or not a court-martial was held and what records exist of the hearing.

So, if you are aware of any information about this particular soldier or his fate, please let us know!

As you may recall, Marsden was a grenadier from the 59th Regiment of Foot. He and his regiment arrived in New England in 1768. However, by 1769 the 59th was in Nova Scotia. A muster roll from October 1770 reveals Marsden was promoted to the rank of sergeant. Unfortunately, by 1774 he was demoted back to a private. The reason for the demotion is unknown but the regimental muster rolls indicate that on July 24, 17774 he deserted from his regiment. Afterward, Marsden fled to Haverhill.

Marsden was the logical choice to train the minute companies of Andover, Bradford and Haverhill. He was intelligent and had extensive experience within the British army. In March and April of 1775, the units actively worked with Marsden to prepare for war. Haverhill initially voted that its minute men “be duly disciplined in Squads three half days in a Week, three hours in each half day.” On March 14, 1775, the town also voted to raise thirty dollars “to procure a military instructor to instruct the Militia in the Art Military.” One week later, it was voted that the minute-men should train one whole day per week, instead of three half days as previously voted. Furthermore, the minutemen were to be trained by a “Mr George Marsden, whom we have hired.”

Interestingly, this is not the only record of a George Marsden being hired to train minute companies in the Merrimack Valley region of Massachusetts. A Haverhill “Independent Corps” commanded by Captain Brickett passed their own resolution “that we hire Mr George Marsdin for 4 days at 12s a day, & that he be paid out of the fines.” Similar records from Andover and Bradford Massachusetts also reference the hiring of George Marsden to train their minute companies.

|

"The Deserter," an engraving by William Dickinson after Henry William Bunbury and published

in London in 1794 by Robert Laurie and James Whittle. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection)

|

After we published our findings, J.L. Bell and Don Hagist brought to our attention another British deserter who had been retained by a Rhode Island militia company to train them in the 1764 Crown Manual Exercise. Yesterday we stumbled across a third British deserter who was possibly training a Freetown, Massachusetts militia company.

Col. Thomas Gilbert was a veteran of the French and Indian War and a staunch loyalist. On the eve of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, he recruited over one hundred men, organized them into a military company and secured stands or arms for them. In early April, residents of neighboring towns received reports that Colonel Gilbert had left Freetown and was planning to return with military reinforcements. A preemptive strike was quickly organized by local minute and militia companies.

According to a Providence newspaper, “that on Monday before, parties of Minute men, etc. from every town in that County, with arms and ammunition, met at Freetown that morning in order to take Col. Gilbert, but he had fled on board the Rose, man of war at Newport.” Ezra Stiles noted that “above a Thousd Men assembled in Arms at Freetown to lay Col. Gilbert as they had heard he had risen up against his Country. They came from all parts round as far as Middleboro, Rochester &c. They took about 30 of his Men & disarmed them, tho' they had lately taken the Kings Arms.”

Shortly after the Freetown Raid, some of Gilbert’s men returned to Freetown and captured a British soldier who apparently had been training the local militia in the “Military Exercise”. According to the Reverend Ezra Stiles, “Some of Col. Gilbert's Men it is said seized a Soldier of the Regulars a Deserter who was teaching military Exercise at Freetown, & were about carrying him to Gen. Gage at Boston.”

At this time it is unknown who this soldier was, what unit he deserted from or what his fate was after his abduction. According to Stiles, there was an attempt to rescue him from his kidnappers. “The Night before last 50 Men marched from Dartmouth to joyn a large Body wath a View to rescue the Soldier.” Whether or not the rescue effort succeeded remains a mystery. Of course, if the deserter was successfully transported to Boston, we’re curious about whether or not a court-martial was held and what records exist of the hearing.

So, if you are aware of any information about this particular soldier or his fate, please let us know!

Thursday, July 25, 2019

"Repugnant to Its Existence" - A Brief Snapshot of the Legal Rights of Enslaved People in Colonial Massachusetts

In 1700, a royal census report indicated that there were over 27,000 enslaved people in the American colonies. Of course, slavery did exist in Massachusetts, and there were slaves living throughout the colony at the outbreak of the Revolution. In fact, slavery had existed in Massachusetts almost from its founding, but the institution had never flourished when compared to the southern colonies.

In some households, male slaves worked side by side with their masters as coopers, blacksmiths, shoemakers, and wheelwrights. In other homes, they ran errands, functioned as valets and performed heavy work for their masters. In Boston, slaves worked closely with sailors and merchants. Female slaves were often required to carry out the various household tasks their mistresses demanded.

Surprisingly, Massachusetts slaves were not without rights. Unlike slaves in the southern colonies, New England slaves could hold property and serve in the militia, as was the case, for example, with five of Lexington’s slaves: Prince Estabrook, Pompey Blackman, Samuel Crafts, Cato Tuder, and Jupiter Tree. However, it wasn’t until the eve of the American Revolution that black men were welcomed into the ranks of the militia. In 1652, the Massachusetts Legislature enacted a law requiring all African-Americans and Indian servants to undergo military training and serve in the militia. Four years later, fearing a slave revolt, Massachusetts reversed the law and prohibited African-Americans providing military service.

Enslaved people could testify in Massachusetts colonial courts against both whites and other blacks, however the weight and value of their testimony were often diminished or discounted because of their status.

A slave could also sue for freedom, as demonstrated by a female mulatto slave named Margaret. On November 20, 1770, Margaret appeared in a court in Cambridge represented by the Boston lawyer Jonathan Sewall. John Adams, who was in the midst of the Boston Massacre trial, represented her masters, the Muzzey family of Lexington. At the end of the hearing, which lasted most of the day, the court freed Margaret.

On rare occasions, enslaved people were also permitted to petition their town selectmen or colonial government for legal assistance. In 1774, several African-Americans addressed the Massachusetts General Court and demanded they be granted the rights and benefits of liberty that their white counterparts were demanding of the crown.

Still, slavery was a degrading and inhumane institution.

By 1643, all of the New England colonies had established laws punishing runaway slaves as “fugitives”. In 1667, England enacted strict laws regulating slavery. A slave was forbidden to leave his master’s property without a pass or permission from his master and never on Sunday. Thus, a slave could not move in search of opportunity or even travel outside of his or her town without the master’s assent. If he were discovered, a slave would be prosecuted as a fugitive. A slave could marry only with the master’s blessing and interracial marriage was illegal.

By 1667, most American colonies had recognized that a slave could not be freed from bondage by baptism, thereby discarding the Christian principle of enslaving other Christians. That same year, the penalty for killing a slave in Massachusetts was a mere £15.

In 1670, the Massachusetts legislature passed a law permitting slaveholders to sell children of slaves into bondage. Thus, a slave, as well as his wife and children, could be sold to another owner at his master’s whim. As late as 1774, the seaside town of Newburyport was hosting auctions for the sale of child slaves.

Finally, a slave was always subject to both actual and potential cruelty against which there was no defense. On Boston Neck, travelers were presented with the view of a cage containing the bones of Mark, a slave who had been convicted of murdering his master. The spectacle was intended to serve as a constant reminder to slaves in Massachusetts of the potential penalties for defiance. If a slave struck a white man, he would be summarily and severely punished. Even worse, by 1682, most American colonies prohibited slaves from asserting self-defense in criminal prosecutions.

By the start of the 18th Century, prominent Massachusetts officials recognized the evils of the practice and called for an end to it. In 1700, Chief Justice Samuel Sewall of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court published The Selling of Joseph, a book outlining the economic and ethical grounds for abolishing slavery. In 1764, James Otis, a leading proponent of colonial independence, wrote in a highly regarded and influential pamphlet "The colonists are by the law of nature freeborn, as indeed all men are, white or black."

Unfortunately, it was not until 1783, through a series of cases known as "the Quock Walker Case," that slavery was abolished in Massachusetts. As Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice William Cushing asserted "[S]lavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it [is] wholly incompatible [with the Massachusetts Constitution] and repugnant to its existence."

In some households, male slaves worked side by side with their masters as coopers, blacksmiths, shoemakers, and wheelwrights. In other homes, they ran errands, functioned as valets and performed heavy work for their masters. In Boston, slaves worked closely with sailors and merchants. Female slaves were often required to carry out the various household tasks their mistresses demanded.

Surprisingly, Massachusetts slaves were not without rights. Unlike slaves in the southern colonies, New England slaves could hold property and serve in the militia, as was the case, for example, with five of Lexington’s slaves: Prince Estabrook, Pompey Blackman, Samuel Crafts, Cato Tuder, and Jupiter Tree. However, it wasn’t until the eve of the American Revolution that black men were welcomed into the ranks of the militia. In 1652, the Massachusetts Legislature enacted a law requiring all African-Americans and Indian servants to undergo military training and serve in the militia. Four years later, fearing a slave revolt, Massachusetts reversed the law and prohibited African-Americans providing military service.

Enslaved people could testify in Massachusetts colonial courts against both whites and other blacks, however the weight and value of their testimony were often diminished or discounted because of their status.