James McAlpin was the only son of New York loyalists Daniel and Mary McAlpin. Born in 1765, McAlpin resided with his parents and sisters in Stillwater, New York. In May of 1774 his father purchased approximately one thousand acres of land located on the west side of Saratoga Lake (in the present Town of Malta) and immediately proceeded to improve upon it. The McAlpin family moved to their new home in 1775. By 1776, the family was already building a second home on the property.

At the outbreak of the American revolution, the McAlpin family was firmly in support of the British Crown. As a result, the family was subjected to a series of escalating hostile acts at the hands of a local rebel organization known as the “Tory Committees”. When local officials discovered that Daniel McAlpin was recruiting loyalist soldiers and attempting to send them to Canada, a bounty of $100 was set for his capture of McAlpin. Captain Tyrannis Collins of the Albany County Militia was ordered to arrest McAlpin and “carry [those] who were supposed to be disaffected to the country, as prisoners to Albany.”

Realizing he had been exposed, Daniel McAlpin was forced to flee to the safety of without his family. McAlpin remained in hiding in a cave until Burgoyne’s army arrived at Fort Edward in August, 1777. However, shortly after his escape, Daniel McAlpin’s property was seized and his wife and family were arrested. Mary McAlpin described her family’s treatment at the hands of the rebels in vivid language. “From the day her husband left to the day she was forced from her home the Captain's house was never without parties of the Rebels present. They lived at their discretion and sometimes in very large numbers. They destroyed what they could not consume. . . a group of armed Rebels with blackened faces broke into the McAlpin's dwelling house. They threatened Mary and her children with violence and menace of instant death. They confined them to the kitchen while they stripped every valuable from the home. A few days after this, by an order of the Albany Committee, a detachment of Rebel Forces came and seized upon the remainder of McAlpin's estate both real and personal.” Mary McAlpin and her children were taken to an unheated hut located in Stillwater and locked inside “without fire, table, chairs or any other convenience.”

Hoping that the hardship would eventually break Mrs. McAlpin and induce her to beg her husband to honorably surrender, the rebels kept Mary and her children in captivity for several weeks. Mary McAlpin refused to comply and instead responded her husband “had already established his honour by a faithful service to his King and country.” Enraged, rebels seized Mary and her oldest daughter and “carted” both of them through Albany. According to one witness “Mrs. McAlpin was brought down to Albany in a very scandalous manner so much that the Americans themselves cried out about it.” A second account stated “when Mrs. McAlpin was brought from the hut to Albany as a prisoner with her daughter . . . they neither of them had a rag of cloaths to shift themselves.”

At some point during the Burgoyne invasion, the McAlpin family was released from rebel custody and joined their father. While Mary and her daughters fled to Canada, James remained behind and joined the military unit his father now commanded: The American Volunteers. In October, 1777 at the mere age of twelve, James McAlpin was appointed to the rank of ensign. It is unknown what combat experience, if any, James had in the final days of the Burgoyne Campaign. Nevertheless, James remained on the American Volunteers muster rolls as an ensign for the next three years.

On July 22, 1780, Daniel McAlpin succumbed to a long illness and passed away. In the aftermath of his death, many loyalist officers directed their attention towards James. It is possible that while alive, James’ father either failed to ensure his son received proper training as an officer or covered his son’s gross incompetence. Major John Nairne, who succeeded Daniel McAlpin as commander of the American Volunteers, expressed concern that the young officer was completely out of his element. “[His] time is quite lost while he stays here & I beg you may contrive as much business for him as possible, only (as he is young) that he may not be exposed to much fatigue, or to be lost in the woods.” As a result, Nairne suggested to Lieutenant William Fraser that McAlpin be transferred out of the American Volunteers and sent to a loyalist post at Vereche “to be employed on some Military Duty, and also in Writing and accompting.” General Frederick Haldimand approved of the order but noted “how very young a Boy Mr. McAlpine is.” However, he insisted that “by the time [McAlpin] knows a little of his duty he will succeed to a lieutenancy.”

On December 1, 1780, James McAlpin was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 1st Battalion of the King’s Royal Regiment. He was posted to the prison island of Coteau du Lac and was placed under the command of Captain Joseph Anderson. McAlpin oversaw thirty soldiers, a block house and an unknown number of American prisoners of war.

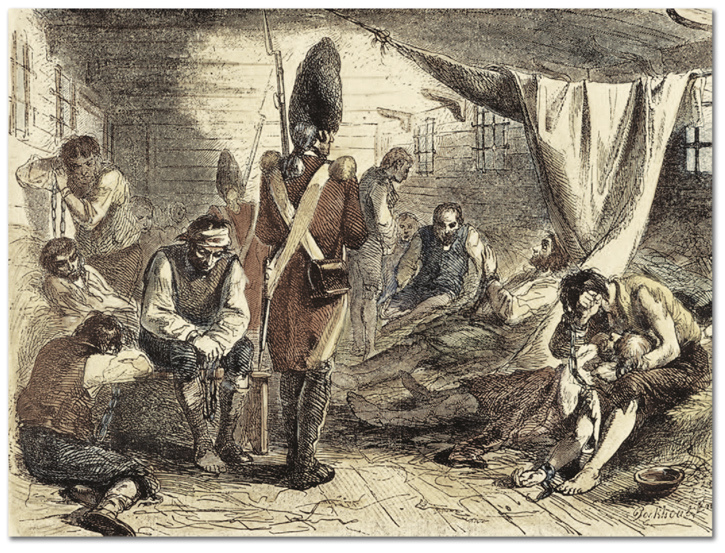

While stationed at Coteau du Lac, McAlpin discovered that several of the American prisoners under his care were involved in the plundering of his family home and abuse of his mother and sisters. In February, 1782, an intoxicated McAlpin had the offending prisoners “strung up” and tortured. Upon sober reflection, the young officer realized his mistake and begged forgiveness from the prisoners.

In the early summer of 1782, five American prisoners escaped from Coteau du Lac. On June 10th, two of the escapees were apprehended by German soldiers. The poor physical and mental condition of the Americans was immediately apparent. When interviewed, the prisoners recounted to German officers their treatment at the hands of McAlpin. Specifically, the men described a lack of how McAlpin deprived them of soap, proper food, clothing, shoes, tobacco and other provisions.

Brigadier General Ernst Ludwig Wilhelm De Speth immediately reported the incident to Haldimand. In response, Major Gray and four captains were dispatched to Coteau du Lac to investigate the claims. Both soldiers and prisoners reported to Gray that McAlpin was often intoxicated and treated the American prisoners poorly. Although in his report Gray noted many of the prisoners were insolent, the ensign was quickly arrested.

On July 15, 1782, Haldimand noted in his general orders that McAlpin was to be subject to a court martial due to the “most barbarous and inhumane treatment of prisoners.” During the hearing, American prisoners testified how food provided to them was crawling with vermin, blankets and straw were intentionally withheld and many were deprived of the simple necessity of water. As one prisoner recounted “some of the men became so dry and thirsty they were attacked with the raising of the blood.” Another described that because of the poor treatment at the hands of McAlpin, he would likely be a “cripple for the remainder of his life.”

The court quickly ruled that Ensign McAlpin was “guilty of the crime laid to his charge in breach of the twenty-third article of the fifteenth section of the articles of war.” He was immediately sentenced “to be Dismst his Majestyes Service.” James McAlpin’s military career ended at the age of seventeen.

Why McAlpin abused the prisoners under his charge is somewhat unknown. One potential motivating factor was likely his family’s treatment at the hands of the Americans back in New York. Another possible cause was his father’s failing health and ultimate death, both of which were likely caused by Daniel McAlpin being forced to hide in caves and woods from patriot forces. Given his young age, McAlpin also could have been easily influenced by the soldiers under his command. Finally, a lack of proper training and guidance from his superiors may have contributed to his actions.

Shortly after his conviction, James McAlpin, as well as his four sisters and mother, left Montreal and sailed for England. None of the McAlpins ever returned to America. Instead, the family took up initial residence in London. In her Loyalist Petition claim, Mary McAlpin makes little to no reference of her son or his military career. Instead, she focuses on the hardships of her husband, daughters and herself. It appears that James never submitted his own claim to the English government. Thus, what became of the disgraced officer after his arrival in England remains a mystery.

No comments:

Post a Comment