Not surprisingly, the records contain claims submitted in 1775 and 1776 for arms and equipment lost or damaged during the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

As we reviewed the legislature’s response to these petitions, we discovered several claims from Lexington militia men or their family asserting that in the aftermath of the battle, British troops looted the dead and wounded of their arms and equipment.

For example, John Tidd asserted “on the 19th of April he received a wound in the head (by a Cutlass) from the enemy, which brought him (senceless) to the ground at wch time they took from him his gun, cartridge box, powder horn &c.” Thomas Winship, who was wounded in the engagement, sought compensation for a “sum of one pound for shilling sinfull for a gun lost in the Battle of Lexington.”

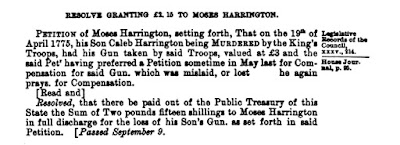

Lucy Parker submitted a claim on behalf of her deceased husband, Jonas Parker. In her appeal, she listed “a musquet, &c. Taken from her husband.” Jonathan Muzzy submitted a petition on behalf of his son who was killed in the engagement. In his application, he listed “a gun, powder horn, &c. Taken from his son.” Another father, Moses Harrington, noted that “his son Caleb Harrington was MURDERED by the King’s troops, had his gun taken by said troops, valued at £3.”

Of course, it should be noted that the claims we found were not limited to the dead and wounded. Fifty-four-year-old militiaman Marrett Munroe asserted he had “a gun & hat taken from him.” Munroe was not injured during the battle so we suspect he may have lost or discarded these items as he fled off the town common.

Benjamin Wellington, who was captured by an advance British patrol prior to the Battle of Lexington, also submitted a claim for property taken from him. As the milita man reported, a “gun, bayonet, &c.” were stolen from him after he was detained.

So why were British soldiers seizing Lexington arms and equipment? Lieutenant Colonel Smith in his official report to General Gage noted one of the purposes of the light infantry advancing on Captain Parker’s Company was “to have secured their arms.” Similarly, Major Pitcairn ordered his troops to “not to fire, but surround and disarm them.” So it is likely the soldiers were simply following orders to disarm the militiamen they encountered.

A more plausible explanation is that the light infantry simply wanted to remove any potential threat by disarming those militiamen, dead or alive, who remained on the field as well as collect any weapons and accoutrements that were abandoned during the fight.

Of course, on a slightly related note, the nerds are excited to have found these claims as they collectively represent yet another snapshot of Captain Parker’s Company at the Battle of Lexington. For several years we have asserted that the town's militia was not sparsely armed and equipped and took the field prepared for a military campaign.

These legislative records are yet another step closer to proving this theory.

As we reviewed the legislature’s response to these petitions, we discovered several claims from Lexington militia men or their family asserting that in the aftermath of the battle, British troops looted the dead and wounded of their arms and equipment.

For example, John Tidd asserted “on the 19th of April he received a wound in the head (by a Cutlass) from the enemy, which brought him (senceless) to the ground at wch time they took from him his gun, cartridge box, powder horn &c.” Thomas Winship, who was wounded in the engagement, sought compensation for a “sum of one pound for shilling sinfull for a gun lost in the Battle of Lexington.”

Lucy Parker submitted a claim on behalf of her deceased husband, Jonas Parker. In her appeal, she listed “a musquet, &c. Taken from her husband.” Jonathan Muzzy submitted a petition on behalf of his son who was killed in the engagement. In his application, he listed “a gun, powder horn, &c. Taken from his son.” Another father, Moses Harrington, noted that “his son Caleb Harrington was MURDERED by the King’s troops, had his gun taken by said troops, valued at £3.”

Of course, it should be noted that the claims we found were not limited to the dead and wounded. Fifty-four-year-old militiaman Marrett Munroe asserted he had “a gun & hat taken from him.” Munroe was not injured during the battle so we suspect he may have lost or discarded these items as he fled off the town common.

Lieutenant William Tidd, who also escaped the engagement unharmed, submitted a petition asserting his “losses by the Kings troops on the 19th of April 1775 … [included] ... a musket cut as under &c.” In a deposition years later, Tidd recalled being chased from the green by an officer on horseback. He claimed “I found I could not escape him, unless I left the road. Therefore I sprang over a pair of bars, made a stand and discharged my gun at him; upon which he immediately turned to the main body, which shortly after took up their march for Concord.”

It is possible Tidd lost his possessions as he hurdled over the fence. As for the “musket cut as under”, this appears to be a reference to a damaged gun. Whether this occurred at the battle or later in the day is unknown.

Benjamin Wellington, who was captured by an advance British patrol prior to the Battle of Lexington, also submitted a claim for property taken from him. As the milita man reported, a “gun, bayonet, &c.” were stolen from him after he was detained.

So why were British soldiers seizing Lexington arms and equipment? Lieutenant Colonel Smith in his official report to General Gage noted one of the purposes of the light infantry advancing on Captain Parker’s Company was “to have secured their arms.” Similarly, Major Pitcairn ordered his troops to “not to fire, but surround and disarm them.” So it is likely the soldiers were simply following orders to disarm the militiamen they encountered.

A more plausible explanation is that the light infantry simply wanted to remove any potential threat by disarming those militiamen, dead or alive, who remained on the field as well as collect any weapons and accoutrements that were abandoned during the fight.

Of course, on a slightly related note, the nerds are excited to have found these claims as they collectively represent yet another snapshot of Captain Parker’s Company at the Battle of Lexington. For several years we have asserted that the town's militia was not sparsely armed and equipped and took the field prepared for a military campaign.

These legislative records are yet another step closer to proving this theory.