On today’s episode, we’ll discuss the often-overlooked battle of the American Revolution - the May 1775 Battle of Chelsea Creek.

On today’s episode, we’ll discuss the often-overlooked battle of the American Revolution - the May 1775 Battle of Chelsea Creek.

The Nerds rarely get involved in the politics of reenacting. Honestly, we have better things to do with our time.

However, a video promoted earlier this week by a non-profit historical organization has caused a bit of a kerfuffle within the living history community. The now-deleted video in question depicted a group of reenactors portraying privateers (although fantasy pirates is probably a more apt description) engaged in a tactical demonstration. At the height of the engagement, and to the humor of the spectators and participants, a reenactor comically mimicked a wound to the groin.

It was clear by his subsequent conduct the display was done to entertain reenactors and the spectators alike. In their defense, the non-profit organization that supervised these reenactors argued that the incident occurred during a “private” tactical for reenactors, the public never saw these antics and those who objected are overreacting.

We get that argument and understand where they are coming from. The Nerds are quite confident there are several images or photos of us acting like idiots and yahoos at private events hosted by reenactment groups from the past thirty-plus years.

However, the problem is the non-profit organization posted the now infamous groin wound incident on a very public Facebook page and encouraged others to revel in the humor and share the experience with their friends.

|

| Taken From Pension Application of Veteran Solomon Parsons |

Let’s be blunt...we wouldn’t mock the experiences of a wounded Iraq War veteran, a Vietnam War veteran or a World War II veteran. Why is it acceptable to mock and make light of the experiences of the wounded from the American Civil War or American Revolutionary War?

Thanks to the romanticism of the 19th century, many people are oblivious of just how vicious and brutal combat during the American Revolution truly was. All one has to do is look at the aftermath of the Menotomy Fight of April 19, 1775, or the Battle of Oriskany to get even the slightest understanding of how destructive 18th-century combat truly was.

Furthermore, the mocking of the wounded through comical antics only serves to trivialize the sufferings of those soldiers who received debilitating wounds during the war.

How does mimicking a wound to the groin for the sake of humor bring to light the sufferings of Massachusetts Soldier Solomon Parsons? At the Battle of Monmouth, Parsons was bayoneted and shot multiple times by British soldiers before being dragged through the dirt, robbed and left for dead. As he laid suffering in an open field and exposed to the blazing hot weather, all Parsons could do was weakly plead for mercy as his assailants continued to taunt and dehumanize him. He was eventually rescued by American troops.

Perhaps the promoters of the “groin video” could explain how mocking the wounded highlights the sufferings of John Robbins. At the Battle of Lexington, Robbins suffered a debilitating wound that left him virtually a ward of the state for the remainder of his life. According to one of his earlier petitions, “That your Petitioner was on the memorable 19th of april 1775 most grievously wounded. by the Brittish Troops in Lexington, by a musket ball which passed by the left of the spine between his Shoulders through the length of his neck making its way through and most miserably Shattering his under jaw bone, by which unhappy Wound your Petitioner is so much hurted in the Muscles of his shoulder, that his Right arms is rendered almost useless to him in his Business and by the fracture of his under jaw the power of Mastecation is totally destroyed and by his, low Slop diet, weakness, and total loss of his right arm, and the running of his wound, his Situation is rendered truly Pitiable being unable to Contribute any thing to the Support of a wife and five small Children but is rather a Burden upon them.”

It is no secret that the Nerds are fascinated with research studies and reports that explore the civilian experience of the American Revolution. Of particular growing interest has been the retelling of both important and mundane events from the perspective of child witnesses.

Admittedly, the Nerds are unaware of any existing primary accounts from children that document the Battle of Bunker Hill. Instead, most, if not all of the accounts from children first surfaced in the early to mid 19th Century and are understandably subject to careful scrutiny. Similarly, by the middle to late 19th Century, grandchildren of witnesses began to share the stories of their elders.

Many historians rightfully argue that these 19th-century accounts may be tainted by either fading memories or a desire to exaggerate or sensationalize one’s role during the early months of the American Revolution. As 19th Century Massachusetts historian George E. Ellis noted, many veterans and witnesses who claimed to have participated in the Battle of Bunker Hill, "Their contents were most extraordinary; many of the testimonies extravagant, boastful, inconsistent, and utterly untrue; mixtures of old men's broken memories and fond imaginings with the love of the marvellous. Some of those who gave in affidavits about the battle could not have been in it, nor even in its neighborhood. They had got so used to telling the story for the wonderment of village listeners as grandfathers' tales, and as petted representatives of 'the spirit of '76’, that they did not distinguish between what they had seen and done, and what they had read, heard, or dreamed. The decision of the committee was that much of the contents of the volumes was wholly worthless for history, and some of it discreditable, as misleading and false."

With that context in mind, the Nerds would still like to highlight an account we came across approximately two years ago from Loyalist Dorthea Gamsby regarding her memories of June 17, 1775. Admittedly we completely forgot about Gamsby’s story until we were preparing for a History Camp presentation.

Loyalist Dorothea Gamsby was the daughter of John and Margaret Gamsby and the niece of Sir John Nutting. She arrived in Boston with her aunt and uncle at some point before April 1773. At the time of the Battle of Bunker Hill, she was only ten years old.

Allegedly, Dorothea’s granddaughter, a “Mrs. Marcus D. Johnson”, recorded Dorothea’s recollections of her experiences in Boston at some point in the 1830s or 1840s. The accounts were eventually turned over to Dorothea’s great-grandson, Charles D. Johnson, the editor and publisher of a North Stratford, New Hampshire newspaper entitled The Coos County Democrat. Dorothea’s account appeared in that newspaper as a series of articles between 1859 and 1862.

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities in 1775, Dorothea noted that “My uncle took a beautiful house in one of the pleasantest streets in Boston, my father went into business in Lynn a town not far off. I never visited the place but once or twice and recollected very little about it, for the country my uncle said, had gone mad, and we had better stay at home. In fact, it was on the eve of revolution, and we were visited by noble looking gentlemen without number, who talked all dinnertime of the rebelious whigs, and what the parliament had done and would do.”

Dorothea’s account to her granddaughter does discuss the Boston Tea Party but does not recount any of the subsequent political or military conflicts until the Battle of Bunker Hill. Curiously, she does reflect upon the growing tensions between the troops stationed in Boston and the town’s civilian population. As Gamsby observed “They sent a host of troops from home. Boston was full of them, and they seemed to be there only to eat and drink and enjoy themselves.”

In the early hours of June 17, 1775, Dorothea was woken from her sleep. According to her statement “one day there was more than usual commotion, uncle said there had been an outbreak in the country; and then came a night when there was bastle, anxiety, and watching. Aunt and her maid, walked from room to room sometimes weeping. I crept after them trying to understand the cause of their uneasiness, full of curiosity, and unable to sleep when everybody seemed wide awake, and the streets full of people. It was scarcely daylight when the booming of the cannon on board the ships in the harbour shook every house in the city. My uncle had been much abroad lately and had only sought the pillow within the hour but he came immediately to my aunts room saying he would go and learn the cause of the firing and come again to inform us … We were by this time thoroughly frightened, but uncle bade ‘Keep quiet’ said ‘there was no danger’ and left us.”

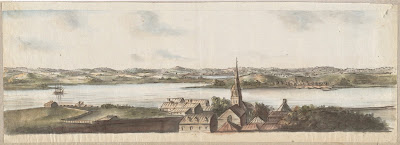

|

| "Charlestown Promontory, the ruins of the town after the Battle of Bunker Hill and General Howe's encampment", c. 1775. |

As the battle raged, Dorothea and her aunt went to an unknown location and apparently had a clear view of the engagement. According to Gamsby, “The glittering host, the crashing music, all the pomp and brilliance of war, moved on up toward that band of rebels, but they still laboured at their entrenchment, they seemed to take no heed- the bullets from the ships, the advancing column of British warriors, were alike unnoticed … Every available window and roof was filled with anxious spectators, watching the advancing regulars, every heart I dare say throbbed as mine did, and we held our breath or rather it seemed to stop and oppress the labouring chest of its own accord so intensely we awaited the expected attack, but the troops drew nearer and the rebels toiled on … At length one who stood conspicuously above the rest waved his bright weapon, the explosion came attended by the crash [illegible] the shrieks of the wounded and the groans of the dying. My aunt fainted. Poor Abby looked on like one distracted. I screamed with all my might.”

As with the pair of child witness accounts from the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Dorothea’s account also reflected upon the horrors of war. “Men say it was not much of a fight, but to me it seems terrible … Charleston was in flames; women and children flying from their burning homes … By and by, drays, carts and every description of vehicle that could be obtained were seen nearing the scene of conflict, and the roar of artillery ceased. Uncle came home and said the rebels had retreated. Dr Warren was the first to fall that day. Then came the loads of wounded men attended by long lines of soldiers ... a sight to be remembered … there is nothing but woe and sorrow and shame to be found in the reality.”

Dorothea Gamsby remained in Boston until the evacuation of March 17, 1776. Afterward, she resided first in Nova Scotia and then in Quebec. Eventually, she, her husband, and her children returned to the United States and settled in Vermont.