By 1775, Lexington was not immune to the institution. The largest slaveholder in 1771 was Samuel Hadley with three enslaved servants. Other slaveholders included Samuel Bridge, William Tidd, Robert Harrington, William Reed and Benjamin Estabrook.

In some Lexington households, male slaves worked side by side with their masters as coopers, blacksmiths, shoemakers and wheelwrights. In other homes, they ran errands, functioned as valets and performed heavy work for their masters. The few female slaves in Lexington were required to carry out the various household tasks their mistresses demanded.

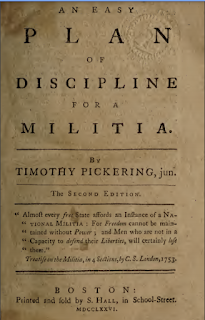

The enrolling of enslaved men in the colony’s militia system was considered illegal on the eve of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. In 1652, the Massachusetts Legislature enacted a law requiring all African-Americans and Indian servants to undergo military training and serve in the militia. However, four years later, as fears of a slave revolt grew, Massachusetts reversed the law and prohibited Blacks from entering military service. According to research conducted by Minute Man National Historical Park, In 1709, the Massachusetts legislature slightly reversed itself and declared that “free male negro’s or molattos” would be exempt from military training but would still be required to “make their appearance” with their local militia companies “in case of alarm”.

Nevertheless, in 1775, Lexington turned a blind eye to the law. As a result, during the War for Independence, five of Lexington’s slaves served with the town's militia. These enslaved men were Prince Estabrook, Pompey Blackman, Samuel Crafts, Cato Tuder and Jupiter Tree.

As an aside, there was a Lexington Black freeman, Eli Burdoo, who later asserted in a pension claim that he served Captain Parker’s Company at the Battle of Lexington.

Lexington slaves were not completely without rights. Unlike slaves in the southern colonies, New England slaves could hold limited amounts of property, and testify in court against both whites and other Blacks.

On rare occasions, Massachusetts slaves were permitted to sue for freedom. One such case involved a female mulatto slave named Margaret from Lexington. On November 20, 1770, Margaret appeared in a court in Cambridge represented by a local Boston lawyer named Jonathan Sewall. John Adams, who was currently in the midst of the Boston Massacre trial, represented her masters, the Muzzey Family of Lexington. At the end of the hearing, which lasted most of the day, the court freed Margaret.

In 1774, several African-Americans petitioned the Massachusetts General Court to demand that they too have the right to enjoy the benefits of liberty.

Still, slavery was a degrading and inhumane institution.

By 1667, most American colonies had recognized that a slave could not be freed from bondage by baptism, thereby discarding the Christian principle of enslaving other Christians. That same year, the penalty for killing a slave was a mere £15. In 1670, the Massachusetts legislature passed a law permitting slaveholders to sell children of slaves into bondage.

By the middle of the 17th Century, all of the New England colonies had established laws punishing runaway slaves as “fugitives”. Under these anti-fugitive laws, a slave was forbidden from leaving his master’s property without a pass or permission from his master. Travel on Sunday was explicitly prohibited. Thus, a slave could not even move in search of opportunity or even travel outside of Lexington without the master’s assent. If he or she were discovered, the enslaved person would be prosecuted.

Finally, a slave was always subject to both actual and potential cruelty against which there was no defense.

Understandably, these horrific conditions motivated many enslaved people from New England to run away from their masters. In turn, slaveholders would publish advertisements in area newspapers describing the enslaved person, the clothing they wore when last seen and any items they carried with them.

Understandably, these horrific conditions motivated many enslaved people from New England to run away from their masters. In turn, slaveholders would publish advertisements in area newspapers describing the enslaved person, the clothing they wore when last seen and any items they carried with them.

In the work Escaping Bondage: A Documentary History of Runaway Slaves in Eighteenth Century New England 1700 - 1789, author Antonio Bly catalogs advertisements of runaway Black slaves that appeared in Eighteenth-Century New England newspapers.

There are four newspaper advertisements Bly identifies that are tied to Lexington. The first three were published by Captain Benjamin Reed after his slave “Sambo” or Samuel Hanks escaped. Reed was particularly determined to apprehend the runaway as he flooded Boston area newspapers with advertisements seeking his slave’s capture.

Here is Reed’s advertisement from the September 17, 1753 edition of the Boston Gazette:

“Ran-away from his Master Capt. Benjamin Reed, of Lexington, on the 14th of this Instant September, a Negro Man Servant, named Sambo, but calls himself Samuel Hank’s, and pretends to be a Doctor, about 30 Years of Age, of a middling Stature, speaks good English: Had on when he went away, a brown homespun Coat with brass Buttons, a brown Holland Jacket, new Leather Breeches, a pair a blue clouded seam’d Stockings, a new course Linnen Shirt, and a Holland one, Trowsers, and an old Castor Hat: has lost some of his fore Teeth. He carry’d with him a Bible, with (Samuel Reed) wrote in it, with some other Books. Whoever shall take up said Runaway Servant, and convey him to his abovesaid Master in Lexington, shall have Four Dollars Reward, and all necessary Charges paid. And all Masters of Vessels and others are hereby caution’d against concealing or carrying off said Servant on Penalty of the Law. Lexington.”

Bly’s book also identifies an incident that involved Lexington tavern owner John Buckman. The account appeared in the January 18, 1776 edition of the New England Chronicle. According to the newspaper account, an eighteen-year-old male slave named Cato had escaped from Hampton, New Hampshire in the Fall of 1775. Surprisingly, Cato did not flee to Portsmouth or Newburyport to join a sailing vessel (18th century New England sailing vessels were notorious for taking on escaped Black slaves). Instead, he traveled into the Massachusetts interior and by November 1775, arrived in Lexington.

According to the New England Chronicle, Cato approached John Buckman seeking work. “He offered his service to Mr. John Buckman, innholder in that town, and called himself Elijah Bartlet, and said that he was free born.” Buckman was suspicious of the young man and believed Cato was “a runaway”. Aware that the tavern keeper was on to him, Cato “stopped but a few days [in Lexington], and went off privately.” It appears after Cato fled, the Buckman reported the runaway to the authorities, who in turn relayed the information to Cato’s owner.

As far as the Nerds can tell, Cato was never apprehended.

Bly’s book also identifies an incident that involved Lexington tavern owner John Buckman. The account appeared in the January 18, 1776 edition of the New England Chronicle. According to the newspaper account, an eighteen-year-old male slave named Cato had escaped from Hampton, New Hampshire in the Fall of 1775. Surprisingly, Cato did not flee to Portsmouth or Newburyport to join a sailing vessel (18th century New England sailing vessels were notorious for taking on escaped Black slaves). Instead, he traveled into the Massachusetts interior and by November 1775, arrived in Lexington.

According to the New England Chronicle, Cato approached John Buckman seeking work. “He offered his service to Mr. John Buckman, innholder in that town, and called himself Elijah Bartlet, and said that he was free born.” Buckman was suspicious of the young man and believed Cato was “a runaway”. Aware that the tavern keeper was on to him, Cato “stopped but a few days [in Lexington], and went off privately.” It appears after Cato fled, the Buckman reported the runaway to the authorities, who in turn relayed the information to Cato’s owner.

As far as the Nerds can tell, Cato was never apprehended.