The Nerds loved Minute Man National Park’s Battle Road 2022. It was a wonderfully well planned and brilliantly executed event.

And without a doubt, the participants that fielded with the composite groups of Captain David Brown’s Company of Concord Minute Men, and Captain Edward Farmer's Billerica Company stole the tactical demonstration aspect of the show. The Nerds considered themselves very fortunate to have the opportunity to field with them and were very impressed with their dedication to authenticity and their commitment to honor those who fought on April 19, 1775.

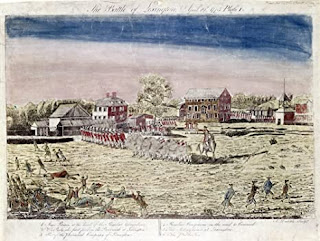

However, there was a another group that deserves praise for their support of this event as well … the Lexington Minute Men, aka Captain John Parker’s Lexington Company. For the past 18 months, the members of this group have been working very hard to revamp their impression and sweep away the inaccurate myths about Lexington’s contributions to April 19th.

While there is always room for improvement, the Lexington Minute Men have a great attitude and are very receptive to constructive feedback. Their level of authenticity is getting better and better each year.

This past April, a new and improved Captain John Parker’s Lexington Company debuted at Battle Road. While many praised the unit, some chastised the organization for their changes and derisively called them “cookie cutters” or said they looked "silly".

To their credit, Lexington responded by pointing to the documentation supporting the proposition their 1775 counterparts most likely carried similar packs, blankets, belting, and cartridge boxes.They also announced they would treat the term "cookie cutter" as a badge of honor.

Anyway, during this year’s activities, the group marched from Lexington Green to the Parker’s Revenge site to honor those from their town who fell during the afternoon skirmish. After the ceremony had concluded, they waited for a bus that was to transport them to the Hartwell Tavern site for a scheduled tactical demonstration.

The unit waited …

And waited …

And waited some more …

But the bus never came.

While many would simply chalk up the demonstration as a washout, the men portraying Parker's Company decided otherwise. Because they felt it was essential to support the event and Head Interpretive Park Ranger Jim Hollister, the men decided they would make the tactical demonstration.

With full gear and muskets, the unit proceeded to RUN a mile and a half across National Park property and entered the field of battle just as His Majesty’s troops were about to clear the field. It was a heck of a sight to see from what we've been told.

So why are we retelling this rather long and possibly story? Because the Lexington Minute Men are also taking a hard look at their annual Battle of Lexington reenactment and asking how they can improve that event and broaden the average spectator's educational experience.

One aspect of the event they want to highlight is the nature of the injuries the wounded men of Lexington received and the long-term suffering that followed them in the months and years after the battle.

Historians Joel Bohy and Dr. Douglas Scott have done admirable work bringing to light the suffering of John Robbins in the aftermath of the Battle of Lexington. If you are not following their research efforts on this topic, you really need to.

But what about the other Lexington wounded? What was the extent of their injuries?

As Mr. Bohy and Dr. Scott noted in an April 20, 2021, guest blog post, “After April 19 and the Battle of Bunker Hill, a few of the wounded men began to ask the state for help. Their wounds, in some cases, made them unable to work and make a living. Medical bills were also growing, and with no income, how could they pay the bills and provide for their families? Many of these petitions for a pension, or after December 1775 for lost and broken material, are in the collection of the Massachusetts State Archives spread through numerous volumes.”

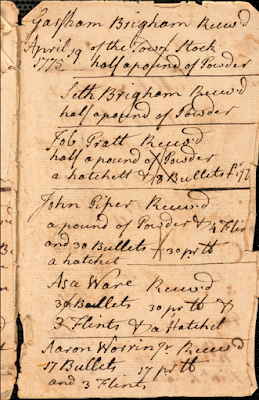

The Nerds recently reviewed the records of the Massachusetts legislature from 1775 and 1776 to see what other Lexington men submitted financial claims s a result of the injuries they sustained. We discovered six out of the nine wounded at the engagement submitted petitions for compensation. Most described the seriousness of their wounds.

As a preliminary matter, let’s examine the damage a standard 18th British infantry musket ball can do to a human body.

According to Bohy and Scott, “Military surgeons in the late 18th and well into the 19th century described and commented on treating gunshot wounds in a variety of texts and treatises. A perusal of some of these texts, as well as the pertinent sections of the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (Part One, Volume 2 and Part 2, Volume 2, 1875 and 1877, respectively) for wound effects of .69-caliber musket balls clearly demonstrate that these large lead balls could indeed inflict significant and lasting effects to hard and soft tissue as well as nerves. Once a ball enters the human body, it can be deflected from a straight path through the tissue by any number of factors and exit the body after a torturous route. This is borne out by our recent live-fire studies of Colonial-era weapons, particularly with the shooting of British land pattern muskets. We observed, using high-speed video recording, that a .69-caliber ball shot at a target 25 to 30 yards away that the ball’s velocity and energy were significant enough to pass through reproduction clothing and 32 inches of tissue simulant. That is the equivalent of the body mass of two people. The ball, on exiting the tissue simulant, still had enough velocity and energy to travel between 50 and 100 additional yards before reaching its terminal velocity.”

So what was the extent of the injuries sustained at the Battle of Lexington?

Bohy and Scott have already explored in great detail the injuries of John Robbins, which can be read here.

According to the Reverend Jonas Clarke, Jacob Bacon of Woburn fielded with John Parker’s Company on April 19, 1775. He was wounded during the morning engagement. Although his 1776 petition to the Massachusetts General Court is missing, the legislative response is not. The General Court ordered, "Resolved That there be paid out of the public Treasury of this Council, Colony to Jacob; Bacon; (à Wounded' Soldier) the sum of Seven - pounds, Nine Shillings, in full for his Nursing, Doctering &c." The order “Nursing, Doctering &c" does create a fair inference that Bacon's injuries were severe enough to require constant medical care and treatment.

Joseph Comee lost full use of his left arm due to the gunshot wound he received. According to his 1775 petition, "that on the 19th of April last, at the battle of Lexington, was by the enemy wounded in the left arm, having the cords and arteries cut in such a manner as to render his arm entirely useless for more than three months, and has been at great charge in surgery, nursing, and board; therefore prays your Honours may grant him such relief as you may think proper”. Shortly thereafter, the Massachusetts General Court resolved "Resolved that of Twelveing and tir Resolved that their be paid out of the Publick Treasury to Joseph; Comee;' the sum of Twelve pounds Seven shillings, in full for his Nursing Boarding, & Doctring and time lost. …”.

Nathaniel Farmer was also wounded in the arm. His injuries were so severe that he never recovered from the wound and remained permanently disabled. According to Farmer’s 1776 petition, "PETITION of Nathaniel; Farmer; of Lexington in the County of Legislative .. Records of the Middlesex Cordwainer humbly Sheweth, that on the morning of the Council, Nineteenth of April last … was fire'd upon by the Ministerial Troops at Lexington, and was Woun[d]ed . in his right Arm wch Fractured the Bone to that degree that sundry Peices of the same has been since taken out, by wch means your Pettioner hath suffered much pain as well as loss of time and Charge to the Docters whose Bills are herewith presented, and in fine is totally disabled from Carrying on his Business, by which he Chiefly supported himself and Family Wherefore he prays your Honours would take his distressed Case, under your wise consideration and grant him such Relief as to you in your Wisdom shall seem meet, and your Petitioner as in duty bound shall ever pray …” In response, the General Court ruled “Resolved that their be paid out of the Publick Treasury of this Colony to Deacon Stone for the Use of Nathaniel; Farmer; the sum of Thirteen pounds Fifteen shillings in full for his Doctring nursing and Loss of time while confined with his Wounds."

In a 1776 stolen property petition, John Tidd described the saber slash he received before being looted by British troops. “On the 19th of April he received a wound in the head (by a Cutlass) from the enemy, which brought him (senceless) to the ground at wch time they took from him his gun, cartridge box, powder horn &c."

Although his petition is silent on the extent of his injuries, Solomon Pierce did require extensive medical treatment, thereby suggesting his wounds were also debilitating. According to a 1776 resolution addressing his petition, the Massachusetts General Court declared, "Resolved that there be paid out of the Public Treasury to Solo mon Pierce;, a wounded' Soldier, the sum of Three pounds Ten shillings, in full for his Nursing, Doctering &c."

Three Lexington men did not submit claims, thereby implying their wounds may not have been severe or debilitating. The Estabrook family did not submit a petition on behalf of their Black slave Prince, although “local legend” repeatedly asserts he was wounded in the shoulder. Thomas Winship also did not submit a claim for his wounds at the battle. Finally, Jedediah Munroe did not file a claim. Regarding Munroe, the injury he received was likely superficial as he was able to field when Parker’s Company re-entered the fighting later that morning.

Sadly, Munroe died at Parker’s Revenge that afternoon.