However, while looking into this matter, we came across yet another petition from a civilian who found herself trapped between hostile forces on April 19, 1775. Before this discovery, we were only aware of three accounts from civilians who found themselves in similar circumstances.

First up is Lincoln’s Mary Hartwell, who remembered coming in close contact with retreating British forces just as they were about to enter the Bloody Curve. “I saw an occasional horseman dashing by, going up and down, but heard nothing more until I saw them coming back in the afternoon all in confusion, wild with rage and loud with threats. I knew there had been trouble and that it had not resulted favorably for their retreating army. I heard musket shots just below by the old Brooks Tavern, and trembled, believing that our folks were killed.”

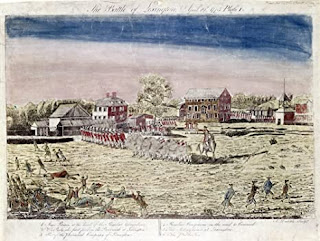

|

| Photo Credit: John Collins |

Anna Munroe, wife of Lexington’s Sergeant William Munroe, and her 5-year-old daughter Anna nearly the Royal Artillery and Percy's Relief Column as they fled the family tavern. According to her 19th Century account, the child witness recalled she “could remember seeing the men in redcoats coming toward the house and how frightened her mother was when they ran from the house. That was all she could remember, but her mother told her of her very unhappy afternoon. She held Anna by the hand, brother William by her side and baby Sally in her arms . . . She could hear the cannon firing over her head on the hill. She could smell the smoke of the three buildings which the British burned between here and the center of Lexington. And she did not know what was happening to her husband, who was fighting, or what was happening within her house. . . Anna’s mother used to talk to her of what happened on April 19th and she remembered that her mother used to take her on her lap and say: ‘This is my little girl that I was so afraid the Red coats would get.’”

Perhaps the most notable female non-combatant who came into direct contact with the retreating British column was Hannah Adams of Menotomy. As we have previously discussed, the Menotomy Fight of April 19, 1775 was a vicious engagement that devolved into a bloody house-to-house and room-to-room fight for survival.

Unfortunately, as this fight raged on, Hannah Adams found herself trapped between Massachusetts militiamen and British regulars.

Hannah had given birth to a daughter approximately ten days before the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The pregnancy and subsequent delivery were particularly difficult; as a result, she was still bedridden on April 19th. As the British column retreated towards her village, her husband, Deacon Joseph Adams, allegedly panicked, abandoned his wife and family, and hid in a nearby hayloft. Three regulars burst into her bedroom at the height of the Menotomy Fight. One threatened to kill her with his bayonet.

According to Hannah Adams, “[Upon] the return of the Kings Troops from Concord, divers of them entered our house by bursting open the doors, & three of the soldiers, broke into the room, in which I then was, laid on my bed; being Scarcely able to walk, from my bed to the fire, & not having been to my chamber-door, from my being delivered in Child-birth to that time -One of the soldiers, immediately opened my Curtains with his Bayonet, fixed, pointing the same to my breast. I immediately cried out –For the Lords Sake, don’t kill me-He replied Damn you-One that stood, near, Said We will not hurt the Woman if she will go out of the house, for we will surely burn it-I immediately arose, threw, a Blanket, over me, went out & crawled into a Corn House, near the door with my infant in my arms, where I remained until they were gone They immediately Set the house on fire, in which I had left five Children, & no other person,-but the fire was happily extinguished.”

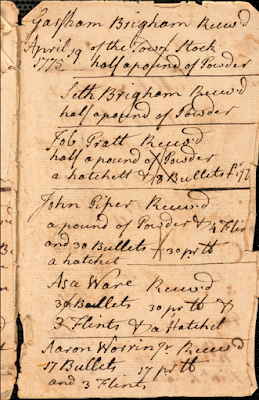

|

| Petition of Hannah Adams, Massachusetts Historical Society |

Adams submitted her account of the encounter to Massachusetts officials, who quickly published it. To say it became a public relations disaster for the Crown in the aftermath of Lexington and Concord is an understatement.

In addition to the account of Hannah Adams, The Nerds recently encountered a description of the Menotomy Fight from a second Hannah - Hannah Bradish of Menotomy.

How we missed her detailed and graphic account is on us. Bad Nerds … Bad Nerds indeed.

Like Hannah Adams, Hannah Bradish was also bedridden on April 19, 1775, having given birth to a child eight days earlier. Her husband, Ebenezer Bradish Jr., was a tavern keeper and part-time attorney. However, unlike Deacon Adams, it appears Bradish’s husband was with his militia company that day.

As the regulars entered Menotomy, Hannah was asleep in bed with her infant. The noise of the fighting woke her up ad she quickly gathered her children and fled to the family kitchen located at the back of the house.

According to her statement submitted to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress on May 11, 1775, “Hannah Bradish, of that part of Cambridge, called Menotomy, and daughter of timothy Paine, of Worcester, in the county of Worcester, esq. of lawful age, testifies and says, that about five o'clock on Wednesday last, afternoon, being in her bed-chamber, with her infant child, about eight days old, she was surprised by the firing of the king's troops and our people, on their return from Concord. She being weak and unable to go out of her house, in order to secure herself and family, they all retired into the kitchen, in the back part of the house. She soon found the house surrounded with the king's troops; that upon observation made, at least seventy bullets were shot into the front part of the house; several bullets lodged in the kitchen where she was, and one passed through an easy chair she had just gone from. The door of the front part of the house was broken open; she did not see any soldiers in the house, but supposed, by the noise, they were in the front. After the troops had gone off, she missed the following things, which, she verily believes, were taken out of the house by the king's troops, viz: one rich brocade gown, called a negligée, one lutestring gown, one white quilt, one pair of brocade shoes, three shifts, eight white aprons, three caps, one case of ivory knives and forks, and several other small articles.”

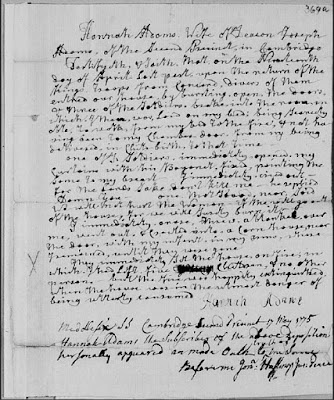

|

| Photo Credit: John Collins |

Of course, the sheer number of bullet strikes into Bradish’s home is corroborated by the Revered David McClure. On April 20, 1775, the minister visited Menotomy and was horrified at the extent of damage he witnessed. “Dreadful were the vestiges of war on the road. I saw several dead bodies, principally British, on & near the road. They were all naked, having been stripped, principally, by their own soldiers. They lay on their faces. Several were killed who stopped to plunder & were suddenly surprised by our people pressing upon their rear…. The houses on the road of the march of the British, were all perforated with balls, & the windows broken. Horses, cattle & swine lay dead around. Such were the dreadful trophies of war, for about 20 miles!”